LB7. One Global Ocean

Chapter 7

{ Losing Biodiversity Contents }

“It is early morning.

I am alone on the deck of the research ship Calypso.

“The sea is flat and grayish-blue. The air is hot and sultry. There is hardly any breeze. Overhead, heavy dark clouds are silently piling up into billowing pyramids…

“What is it about the sea, I wonder as I stare into its depths, that has always lured man on to explore its secrets?

“We are looking there for clues to our own distant past, for information about the formation of our planet and the origin of life. Calypso is crammed with equipment to aid us in that search. Our underwater observation chamber enables us to watch and photograph marine creatures wherever we venture. Divers going down to depths of 200 feet for a firsthand look at the ocean’s habitats enter and leave the water through our midships’ diving-well. Our echo-sounders help us map the ocean floor. Other research vessels have drills that bore into the earth’s crust and bring up cylindrical samples of the ancient material.

We are like detectives trying to unravel what happened millions and billions of years ago.”

– Jacques Cousteau in Ocean World of Jacques Cousteau

I. The Ocean Ecosystem

Perhaps you have been to the ocean and seen a ship disappearing over the horizon as you felt the drumming power of the waves. This pulsating, endless expanse of water serves as a circulatory system for the planet. The water we drink is purified and transformed through the water cycle. The microscopic plants at the surface of the sea convert the sun’s energy to food and produce most of the air we breathe. The ocean is ultimately the source of all life on the planet, yet this vast system is very vulnerable to the impacts of our technological society. This chapter examines how we are reducing the biodiversity of the global ocean.

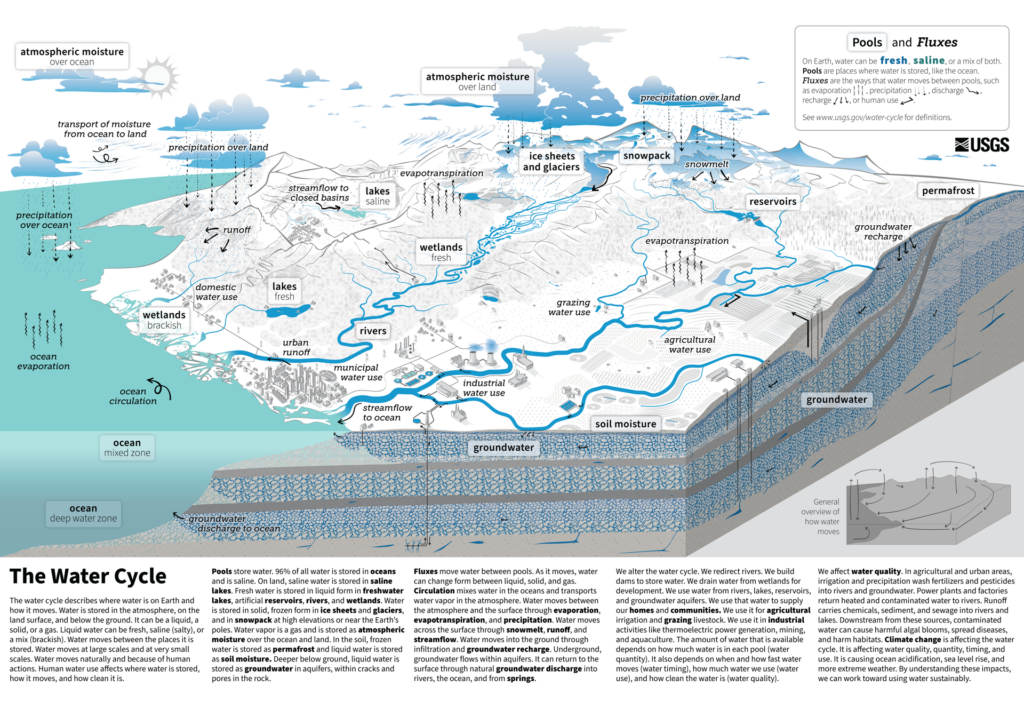

LB7.0. Investigation: The Latest Water Cycle

In October 2022, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) published a new new water cycle diagram. Historically the USGS water cycle diagram is used by hundreds of thousands of students in the United States and worldwide. It’s the basis for many derivative diagrams.

- Compare the older USGS diagram with the new USGS water cycle diagram (see PNG format) and list ways they are similar and ways they are different.

- What parts might be categorized as “natural” (without human influence)?

- What parts might reflect recent research to determine humanity’s role in the cycle?

The ocean is the one feature that distinguishes our planet from all others in the solar system. About three quarters of the Earth’s surface is covered with water. The oceans contain so much water that if all the land surfaces were leveled to fill the ocean gorges and valleys, the planet would be covered with water four miles deep! The open seas may appear to be a limitless resource, but there are huge areas with little life.

Sea water and marine organisms are carried by surface and bottom currents that keep the proportions of the minerals and salts in sea water relatively constant throughout the world ocean. The most productive zones in the ocean are located in areas where nutrient-rich waters rise from the bottom to the surface. These nutrients act as fertilizer, causing blooms of diatoms and algae living in the sunlit surface waters. Cold, nutrient rich water from Antarctica sinks and is pushed along the ocean floor all the way to Newfoundland, Canada where it finally rises up on the steep sides of the Grand Banks, creating one of the richest fisheries in the world.

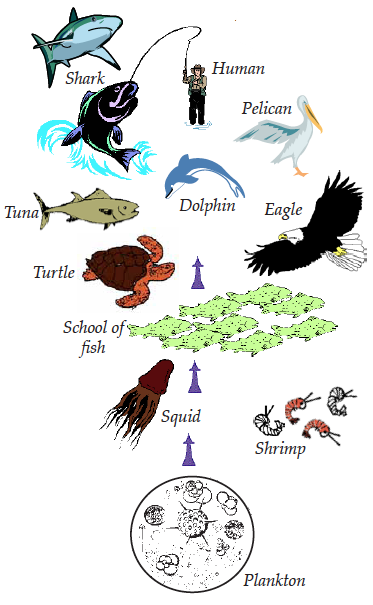

The top hundred meters of the ocean where sunlight flitters down is called the photic zone. This zone contains thousands of species of tiny plants called phytoplankton, which use sunlight to make food for themselves. Phytoplankton serve as food for tiny animals called zooplankton, which are eaten by fish and certain kinds of whales. The fish provide food for hundreds of thousands of seabirds, dolphins, and seals, which serve as food for sharks and other predators. The term “food web” is used to describe the many pathways that energy from plant food is passed along to ever larger animals, as well as to scavengers and decomposers. The great variety of ocean phytoplankton is the main source of food that sustains the vast marine food web.

II. Ocean Explorer Jacques Cousteau

Across the television networks of the world, marine biologist Jacques Cousteau led the public on spectacular treks through the ocean frontiers aboard his research vessel Calypso. Many of today’s marine scientists and educators were stimulated to study the ocean because of this Frenchman’s dynamic example of speaking out and taking action.

Cousteau—photographer, inventor, and educator—was living proof that one person can make a huge difference in changing public attitudes towards the environment. Before his death in 1999, he worked passionately to get the United Nations to adopt an “International Bill of Environmental Rights for Future Generations” modeled after the following document he helped draft in 1979.

International Bill of Environmental Rights for Future Generations

More than 9 million people in more than 70 countries have signed Cousteau’s “Petition for the Rights of Future Generations.”

Article 1.

Future generations have a right to an uncontaminated and undamaged earth and to its enjoyment as the ground of human history, of culture, and of the social bonds that make each generation and individual a member of one human family.

Article 2.

Each generation, sharing in the estate and heritage of the earth, has a duty as trustee for future generations to prevent irreversible and irreparable harm to life on earth and to human freedom and dignity

Article 3.

It is, therefore, the paramount responsibility of each generation to maintain a constantly vigilant and prudential assessment of technological disturbances and modifications adversely affecting life on earth, the balance of nature, and the evolution of humanity in order to protect the rights of future generations.

Article 4.

All appropriate measures, including education, research, and legislation, shall be taken to guarantee these rights and to ensure that they not be sacrificed for present expediences and conveniences.

Article 5.

Governments, non-governmental organizations and the individuals urged, therefore, imaginatively to implement these principles, as if in the very presense of those future generations whose rights we seek to establish and perpetuate.

Learn more about Jacques Cousteau at the Cousteau Society website.

III. Where Have All the Fish Gone?

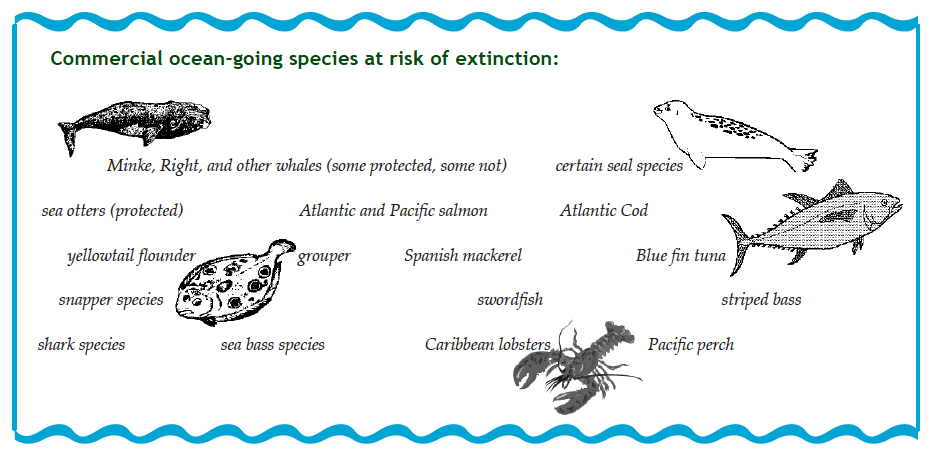

It swims 50 miles per hour, can weigh as much as a cow, and sells for $350 a pound in the sashimi restaurants of Japan. Like the bison of 1880, this graceful fish is nearing extinction, with an estimated population of only 20,000 left in the Atlantic Ocean. If you guessed the bluefin tuna you are correct. Its decline is not due to disease or pollution, but to overfishing. It has recently been proposed for listing as an internationally endangered species.

The once great fisheries of North America and Europe are on the brink of extinction while competing countries, companies and fishermen struggle against environmental regulation.

Where have all the fish gone?

A report released in July 1994 by the WorldWatch Institute, outlined the relationship between increased fishing pressure and the drastic decline in fish populations in many areas of the world. From 1970 to 1990, the world’s fishing fleet doubled, from 585,000 to 1.2 million large boats.

Studies by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation indicate that at least 14 species of oceangoing fish, including Atlantic salmon, cod, yellowtail flounder, grouper, Spanish mackerel and Pacific perch, have been so seriously depleted that it could take them 20 years to recover, even if all fishing were to stop tomorrow.

The declines in fish populations can set off a chain of biological disasters that affect not only the fish but also the animals that feed on them.

Overharvesting is the main cause of the worldwide decline of fish populations. The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) is another international organization that gathers information on global fish harvests. Their studies showed that in 1992, 90.9 million tons of fish came from the oceans, a decrease of 5% from the harvests of 1989. Since then, annual harvests have continued to decline.

New technologies have allowed the competing commercial fleets to fish with more efficiency. Electronic depth finders provide detailed images of the sea floor. Computers “remember” the site of previous good catches, then using radio signals, help boats home in to within 50 feet of that site. Spotter planes and helicopters enable fishermen to hunt down large schools of tuna and other fish. Outside of U.S. waters, gigantic trawlers longer than a football field drag immense gill nets 100 miles long, snaring not only tuna but also swordfish, marlin, dolphins, sharks, sailfish and almost anything that swims.

The pattern is clear–unregulated fishing today means fewer fish tomorrow. The search for solutions is stimulating new approaches to fisheries management. A team of biologists in Florida for example, has recommended setting aside 10 to 20 percent of all coastal waters as “reserves” where fishing is prohibited. Today less than 1% of ocean waters are protected reserves.

A study released February 2001 provides research support for this proposal. The national Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis released findings from 89 marine reserves around the world. The studies showed that, given the chance, fish and other marine life in protected zones quickly restored their populations. Adjacent areas benefited as the populations fanned out from the reserve.

IV. Coral Reefs in Glass Tanks

Coral reefs are the crown jewels of the ocean, adorning islands and coastlines with vibrant colors and fabulous life forms. Tourists travel great distances to swim among coral canyons populated with parrot and clown fish, anemones and sea stars.

Photo by Reginald H. Barrett.

Coral reefs are clearly valued by people from all walks of life, yet these marvelous ocean habitats are in great danger from overharvesting and pollution.

Peoples’ love of reef creatures has stimulated an enormous pet trade industry that threatens to destroy this renewable resource. The U.S. is the world’s largest buyer of tropical fish. More than 10 million hobbyists in this country spend more than 1.6 billion dollars a year on tanks and an estimated 3 billion on pet fish. While most freshwater tropical fish are now bred in captivity, marine organisms are taken from the ocean.

The people who collect reef life for the pet trade often use chemicals like sodium cyanide to stun the fish, as well as destructive tools including dynamite to pull apart the coral reefs.

Marine tanks are often decorated with chunks of dead coral and limestone rock called “live rock,” because the surfaces are covered with living algae, beneficial bacteria, and animals like sponges, tube worms, and sea fans.

The demand for “live rock” and corals is causing reefs around the world to be pulled apart and carved up. An estimated 500 tons of “live rock” were removed from the Florida Reef Track in less than two years.

In 1987, Germany outlawed the importation and sale of butterfly fish, angelfish, lampreys, Moorish idols, corals and clams. Hawaii, Guam, and Puerto Rico have banned the taking and sale of coral and “live rock.” Nations around the world are beginning to take legal action to protect coral reef environments so that they may renew themselves.

Until consumers become better educated about the impact of their purchases of shell jewelry, coral, and reef fish, the thriving business in marine treasures will continue to flourish on the black market.

V. Shrinking Wetlands

Wetlands encircle the continents of the world with salt water marshes, lagoons, and swamps near the mouths of rivers and bays.

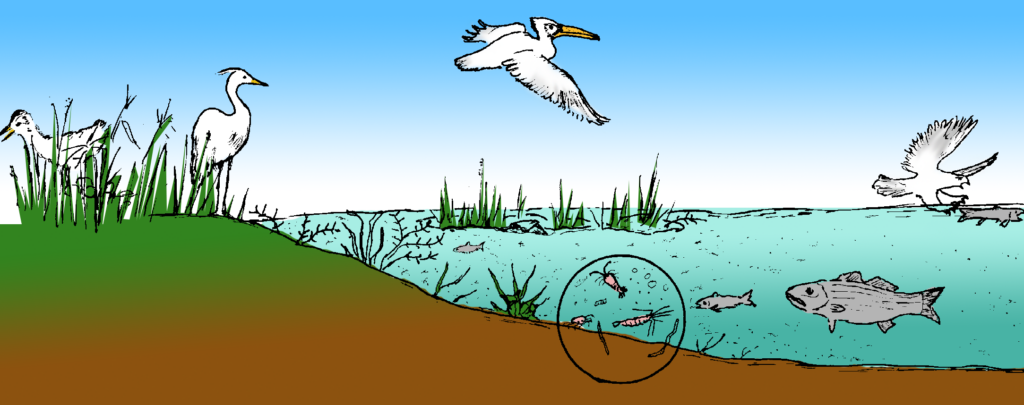

for fish, birds, and other predators like seals and humans

These areas are among the most productive regions of the Earth and are the nurseries for many marine organisms. A tremendous number of organisms have adapted to the special conditions of these marine wetlands, which are alternately flooded with fresh and salt water as the tides ebb and flow.

In the shallow sunlit water, abundant plants use the sun’s energy, water, minerals and nutrients from dead organisms on the bottom to grow and produce more plant matter. This rich plant life feeds teeming populations of mussels, shrimp, baby crabs, and other invertebrates that in turn support fish, ducks, otters, seals, and a host of other wetland animals. Whales, seals, fish, and hundreds of species of ducks, shorebirds, cranes, and song birds migrate thousands of miles across international boundaries to complete their life cycles in the wetlands of North and South America.

Wetlands provide people with hundreds of different products, many of which can be found in your grocery store, such as varieties of shellfish, rice, cat food, and fish. Less well known items include: water chestnuts, fertilizer, vitamins, and caviar.

The most heavily populated areas of the world tend to be along coastlines and near water, consequently, wetlands are among the most reduced and polluted of the world’s ecosystems. Wetlands are difficult to protect, partly because many people have very negative attitudes about these swampy, insect rich areas. Land developers and farmers continue to drain or fill wetlands to increase the land available for farming, housing and industry, and to eradicate insect pests such as mosquitoes. Exotic and beautiful wetland birds like flamingoes, pelicans, egrets, swans and wood ducks have stimulated the most citizen action to save wetland environments.

Beginning in the 1800s, concerned citizens and biologists joined forces to form the National Audubon Society, and their farsighted efforts have led to a number of acts and treaties to protect species and their habitats. The Migratory Bird Treaty of 1916 has resulted in cooperative planning and conservation efforts between Canada, the U.S., and Mexico. There is increasing political pressure to relax conservation regulations protecting these important aquatic resources in order to expand coastal development projects.

Because there is a similar migratory pattern for many of Europe’s endangered species which fly to the wetlands of Africa to spend the winter, and other species that migrate between China, Southeast Asia and Australia, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature was established in the late 1940s to build and lead cooperative conservation efforts between countries. Today the IUCN and other international conservation groups like the World Wildlife Fund are struggling to protect species and their habitats in the face of rapid expansion of urban populations.

VI. Plastic Jellyfish

Sea turtles, like the giant leatherback, have successfully navigated the oceans in search of squid and fish for 300 million years. Populations of these marine reptiles have declined sharply in the last 50 years because of over harvest for turtle soup, accidental drowning in fishing nets, and the loss of protected beaches where they can safely lay their eggs.

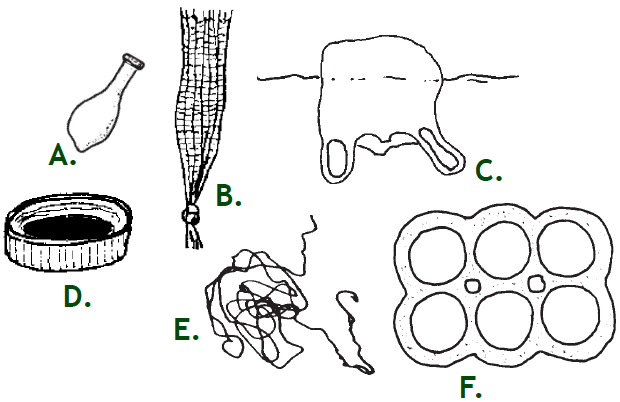

Now their water environment has been invaded by huge populations of party-balloon “squid” and plastic-bag “jellyfish.”

Biologists studying sea turtles frequently find starving animals with giant balls of plastic and fish net lodged in their stomachs. Plastic garbage dumped in the ocean comes in many enticing shapes and colors and has a life span of many years. Many marine animals mistake plastic for food. Each year on the South Pacific island of Laysan, thousands of albatross chicks die when their parents feed them plastic and Styrofoam “fish.” Little piles of plastic debris are left in the nests after the bodies of the baby birds have decomposed.

During the 1980’s the world’s merchant ships, ocean liners, and navy vessels dumped an estimated 690,000 plastic containers into the ocean every day!

Can you identify the types of “plastic jellyfish” that

populate the oceans of the world?

As this tide of plastic covered the world ocean, scientists and environmentalists sounded the alarm. Nets, bags, wrappers, and other debris have been found in the stomachs of whales, dolphins, fish, birds, turtles, manatees, sea lions, and seals. Scientists estimate that plastics kill up to a million seabirds and over 100,000 sea mammals a year. In 1989, the international Marine Pollution Treaty was amended to make it illegal for vessels to dump plastics into the ocean. The U.S. Marine Plastic Pollution Control Act carries a fine of up to $50,000 and five years in jail for dumping plastic at sea.

Even with new laws that prohibit ocean dumping, plastics continue to be the most common kind of litter washed up on beaches. It is difficult to catch ships dumping at sea. However, people around the world are joining citizen action groups to help report the polluters. Every September, all along U.S. coastlines, students and teachers gather for the U.S. Coastal Commission’s Adopt-a-Beach Clean-Up Program. In 1992, the national average of garbage collected during coastal clean-up day was 550 pounds per mile of beach. California averaged 180 pounds per mile, whereas Texas averaged 3,500 pounds of trash per mile.

Since the development of plastic products in the 1940’s, this amazing and versatile substance has replaced many materials such as glass, paper, cloth, and metal. It has become the packaging of choice for the fast food and convenience industry. Because they float, plastic nets, bags, cups, plates and Styrofoam are more easily spread across the ocean. Damaged nets cut loose by fishermen can drift for years. These “ghost nets” even snare large animals like walruses and whales. Catching the people who dump garbage illegally is just one part of the solution. Reducing the amount of plastic that becomes garbage is perhaps an even greater challenge.

In the Mouth of a Whale–A Daring Rescue

A 45-foot humpback whale was drowning in a tangle of a 1,500-foot gill net. The lines were caught in the baleen plates of the whale’s mouth.

“Since I had the most experience in working with whales, it was decided that I would be the one to enter the whale’s mouth….The humpback seemed to sense my apprehension, and held his mouth open above the surface of the water. I climbed in, and tried to get my balance by sitting on the tip of his tongue…I began to remove the threads like so much spent dental floss… This went on for nearly 30 minutes before the net fell away and released him.”

The “plastic issue” begins with you and your family—the consumers. You choose certain products over others for reasons of quality, price, advertising appeal, convenience, and many other reasons. Many people are avoiding buying plastic products because of their impact on ocean life. Recently a major fast food chain announced it was responding to consumer desires for packaging that was less harmful to the environment. This company replaced Styrofoam and plastic food containers with paper packaging. Many plastic products now carry a recycling symbol showing its recycling category. You can encourage companies to recycle by purchasing products made of recyclable plastic. PETE can now be combined with cotton to make T-shirts! Polyvinyl chloride (PV) can be used to make playground equipment.

The issue of plastics in the ocean is a good example of a complex problem without a simple solution. Here are some questions that need to be answered to help consumers make environmentally wise choices:

- How do plastic products compare with other materials with respect to the energy needed to manufacture them and the pollution that they cause?

- To what degree are plastic products being recycled effectively to reduce the amount of waste?

- What are the special qualities of plastics which make them superior to other materials for certain uses?

- What is being done to make plastic products less dangerous to wildlife?

If you look on the bottom of plastic containers, you will find these symbols and codes. In general, the lower the number, the more easily the container can be recycled. Many recycling centers pay a refund for the #1 PETE containers. Find out which plastics your local recycling center will accept.

Plastic Recycling Codes:

PETE #1: polyethylene terephthalate

HDPE #2: high density polyethylene

PV #3: polyvinyl chloride

LDPE #4: low density polyethylene

PP #5: polypropylene

PS #6: polystyrene

Other #7: mixture of plastics

Recycling Fact:

It only takes one incorrectly recycled PV #3 container to ruin an entire batch of recycled PETE #1.

Question 7.1.

How is production, consumption, and disposal of plastics done in your area? Is there a way you can share the information with your community?

VII. How Can Consumers Help?

Logos reprinted with permission from Green Seal and Scientific Certification Systems (SCS). SCS has a hotline for consumer questions about the environment: 1-800-ECO-FACTS

Every time you buy something, your choice has an impact on the environment. Students around the United States discovered their collective power as consumers by leading the “Tuna Boycott.” The stimulus for this student action was a video taken aboard a tuna boat by Sam LaBuddy working undercover as an environmental activist. The film showed the violent death of dolphins caught in the tuna nets. The news media began to cover the grass roots efforts of students around the country, as they brought the issue into their communities and grocery stores.

Responding to the flood of letters from students and the reduction in tuna sales, a leading U.S. manufacturer of tuna announced the company would stop purchasing tuna from fishing boats that netted dolphins. Other manufacturers have responded to the growing public awareness of environmental issues. According to the Marketing Intelligence Service, a company that studies new products, between 1989 and 1991, the number of products claiming to be friendly to the environment nearly tripled. The percent of products that make environmental claims is still less than 20%, but growing steadily.

If you are shopping for food or household items, how can you tell if one product is less environmentally harmful than another? Some companies are making changes to become more environmentally responsible, but sometimes it is difficult to distinguish these companies from pretenders that also claim their products are “green.” In 1990, a nonprofit organization called Green Seal was launched to help shoppers identify honest environmental claims. Modeled after government programs in other countries, this organization develops strict standards for products ranging from motor oil to paper towels.

Green Seal’s staff of scientists, engineers, and attorneys develop technical standards for about 40 categories of consumer products, and invite companies to let Green Seal test their products for a fee. The scientists and engineers consider where the raw materials come from, how the materials are used, the product’s role in the environment and what can be done to make the product less damaging. Products that can meet the Green Seal standards can print its seal of a blue globe with a green check mark on the product packaging.

You may have noticed another environmental label, a green cross over a blue-lined globe, which is the logo for Scientific Certification Systems (SCS). This is a for-profit company that was started in 1984 to certify pesticide levels in produce. SCS has developed a report card that quantifies a product’s environmental burdens and reports them on a chart on the SCS label. This chart allows consumers to compare products making similar green claims.

VIII. Sharing the Ocean Commons

The ocean, like the atmosphere, is an example of a common resource that is shared by people around the world. Without strong international laws and enforcement efforts there is little incentive for some fishing groups to reduce their catch, because competitors will profit by netting the fish left behind. Without global regulations and watchdogs, some shipping companies will try to cut costs by dumping garbage and oil waste at sea. History has shown us that freedom to use a common resource without restraint leads to the extinction of species and the ruin of productive environments.

International cooperation such as the Migratory Bird Treaty has proven essential in developing management systems to sustain resources. Today, the fate of marine fish and marine mammals such as whales and dolphins teeters on the brink of disaster as scientists, conservationists, governments and industry work towards an international management plan for the ocean commons. In the next chapter, we will examine the evolution of stewardship ethics and legal systems for conserving Earth’s biodiversity.

LB7.1. Investigation: Product Research

You can help people in your community learn more about products that claim to have less of an impact on the environment.

- Gather a team of students and decide on a research question and a strategy for carrying it out. For example you might select a category of products such as paper goods, canned fish, or household cleaners. Your team might develop a system that rates the products on the basis of environmental claims and how well those claims are supported.

- Once you have a plan of action, review it with others to get their feedback. The manager of your local grocery store may have useful suggestions for your project.

- How might you determine if the advertising claims are accurate? While making observations of product labels, keep a record of company addresses and telephone numbers so that you can request additional information about the product.

- Share your findings! Write news articles for your school and community newspapers.

Logo for U.S. Department of Commerce

dolphin-safe products