PG8. Choosing a World

Chapter 8

{ Population Growth Contents }

It has been almost two hundred years since Thomas Malthus began the discussion of human population growth.

The discussion continues even today in a world six times more populated than it was in Malthus’ day. Many people are concerned about the problem, but the majority of people are caught up in their day to day lives, paying little or no attention to the issue. Changes caused by population increase take years or decades before they can be noticed. From an individual point of view, it’s easy to overlook global population growth.

To people living in an American small town or rural area, the idea of an overcrowded world probably seems too remote to be concerned about. But in some places, overcrowding is a fact of life.

To people swaying with the movement of a crowded big city subway train, pressed on all sides by the bodies of other people, with strangers’ faces a few inches away from their own, the notion of an overcrowded world is all too real. Personal experience can make all the difference. If we trade places with someone living on a side street in Calcutta, India, we have a quite different personal experience. We are now surrounded by thousands of neighbors, barefoot, sleeping at night in the shelter of a piece of cloth against a wall, searching in garbage cans for a scrap of discarded food. This would give a different perspective on population growth.

Sure, population growth plays a role in the poverty, disease, and environmental degradation that occurs in the less developed world. But sometimes actions far away have profound influence on a local population. Our world is so interconnected that the level of consumption in a rich country can affect the lives of a people living far away, as we may see in the story of Tres Amigos.

I. Tres Amigos

The Valle de San Cristobal lies sixty kilometers southwest of Valencia in the Andean highlands in Venezuela. The valley was the home of about 300 farming families who made their living directly from the soil. Farmers worked small plots of land, called conucos, each about 20 hectares in area (about 45 football fields).

Three of the farmers—Rafael, Jorge and Jose—were friends, all of the same age. They had played together from boyhood. Their adult lives were similar, very much like their fathers before them.

Each had married and became the head of a family that planted the conucos with corn, carrots, black beans and plantain trees. The crops along with chickens and a few pigs made the “tres amigos” self sufficient.

Nearby, Ernesto Sebastian de Cuevas ran a large coffee plantation covering rolling hills with lush, green coffee plants bearing the red coffee beans that made the de Cuevas family wealthy. Ernesto had been worried about the future of his coffee plantation because the yield from his coffee plants was declining. The land was getting tired. Although the quality of his beans was still acceptable, the prices he got for them from the American buyers were not high enough to cover his expenses. Four years ago successive seasons of drought had forced him to borrow money and for the first time in his family’s history there was now a mortgage on plantation de Cuevas. The bank payments were strangling him. At first he thought he might have to move from his comfortable home in Caracas overlooking the Caribbean Sea and return to the plantation to manage the plantation himself, but his friend and banker, Guillen Vincenti, had advised him how to proceed.

In the Llanos, the lands to the south of his plantation, were large ranches there were successfully raising cattle, bringing good prices on the American fast food hamburger market. Americans seemed to be addicted to hamburgers just as they are to coffee. The Valle de San Cristobal with its moist climate and lush vegetation would be an even better place than the Llanos to raise cattle. If he brought cattle raising to the valley he could not only add to his revenue but it could provide a backup should his coffee crop fail again. But for cattle, he needed more land.

Manuel Hernandez, head manager of plantation de Cuevas, had the responsibility to see that de Cuevas’ plans were carried out. His visits to the neighboring conucos had not been encouraging. Only two families had agreed to the price he was offering and were preparing to move out. His next visits to the conucos would not be so friendly, because he had checked at the land office in Valencia and, as he suspected, there were no titles of ownership of the conucos recorded there.

“But what else can I do?” Rafael was talking with his two friends. “If I don’t take the money and work for de Cuevas we will lose everything.”

“How can you think of giving up your land? The land of your father and his father before him?” asked Jorge.

“How can I prove it is mine? The hombre says that de Cuevas has a land grant that is ancient. He says that it includes your conucos too. And Jose’s also.”

Jose bristled, “Let him try to take my land! He will fail!”

“And how will you stop him, my friend?”

The roar of the bulldozer from the plantation filled Jose’s ears as he led his family off the conucos. They carried and wheeled their belongings and tools. The children moved two pigs before them and carried the crates of the few chickens that had not been sold. Jose gave the cart a powerful push. He wanted to get away as quickly as possible, before the bulldozer leveled the house and pushed down the plantain trees his family had carefully nourished for so many years.

The land was all to be converted to growing corn. Not corn that would not be ground up to make delicious arepa but would instead be used to fatten the cattle that were at that moment eating the carrot tops in Rafael’s field. Rafael had taken the job of planting and caring for the corn fields. He was taught to drive a tractor and thus would be able to do the work of ten farmers. He was to be paid in money and would have to buy the corn for his wife, Margareta, to make arepa with.

Jose had warned Rafael, “What will happen if your wages are not enough to buy what you must have?” he had said. “What then? You will go hat in hand to the hombre to beg for more money instead of growing your food yourself! Where is your dignity?”

Jose and his family made their way up the hillside. There, on a slope, Jose had constructed a rude shelter and had begun clearing some of the trees. The land would make a poor farm. It would take months to clear the trees. He would have to find some way to keep the soil from rushing down the slope in the spring rains. The family would have little to eat until a crop, no matter how meager, was planted and harvested. Worst of all there were no plantain trees to give them its sweet fruit. But the land was his. He had made the trip to Valencia and with the money he had been given for his land he bribed a clerk into giving him a deed to a portion of hillside claimed by no one. It would be difficult but Jose was determined that his family would survive.

When the de Cuevas bulldozer came to Jorge’s conucos, he and his family had already left. They had sold everything for a pittance and had taken the long bus ride to Caracas. The bus was crowded with many families doing the same thing. They were going to the big city to find jobs and make a modern way of life for themselves. But there were too many of them.

Around every city in Venezuela, and in other countries in South America, large areas of slums, called barrios, have developed, where squatters from the rural areas live in small shacks. The parents look for odd jobs and children scour the garbage cans for scraps of food. The family finds shelter wherever it can. The squatter shelters are built of boxes and cardboard. There is no easily accessible water and no sanitary facilities. There is not enough work and not enough food. Over three million people live in Caracas and its suburbs. Of them, one million are in the barrios, rural people displaced from their farms. Every day the barrios are growing larger. The government is unable to alleviate the poverty and miserable living conditions.

Some people who say that those living conditions are the result of the desires of the American consumer.

Question 8.1. Do you agree that bad living conditions parts of South America are the result of the desires of the American consumer? If you do, why do you? If you don’t, why don’t you agree?

II. Tragedy of the Commons

The Tragedy of the Commons is the title of an essay by Garret Hardin in which he describes the actions of farmers who jointly own a pasture (“The Tragedy of the Commons,” Garrett Hardin, Science, 162(1968):1243-1248). Each of them sends the greatest number of cows they can to graze on the common land. Since each of them believes that the others will do it, they all do it. The inevitable result is overgrazing and the destruction of the commons. Hardin points out that in each of the farmers’ minds the destruction of the commons is divided up among all the farmers and is therefore small loss to an individual farmer. The fattened cattle bring benefits that are not shared with other farmers but go to the owner only.

Overharvesting the ocean is a “tragedy of the commons” type problem. If there are no restraints, the owners of ocean going factory fishing trawlers believe that it is in their best interest to take as many fish as possible. They reason that if they don’t, someone else will. The injury to the oceans is something that will be divided up by many. The profits from a shipload of fish belongs to the owners only.

In some respects having large families is a “tragedy of the commons” type problem. The benefits that come from having many workers in the family means that the family will be better able to survive and the parents will have security in their old age. These benefits belong to the family alone. The hidden costs of big families such as overcrowding of the land, soil degradation, less water, more illiteracy are shared by the community as a whole.

Environmentalists concerned about the long-range sustainability of the Earth’s systems see the explosion of the human population as a danger. As people all over the world push for a better quality of life for themselves and their children they are pressing against the ability of the Earth to supply water, food, space and manufactured goods. It is not necessarily the numbers of people that are the problem. It is what an increase in population does to the environment in order to meet their needs that are a cause for concern.

III. Quality of Life

The fact that modern civilization extends the human life span and brings improvements in living conditions for many people cannot be denied. That it does not improve living conditions for everyone also cannot be denied. It is difficult to measure “quality of life.” One measure can simply be the change in average life expectancy. Other measures can be a reduction in the rate of infant mortality, gross national product (GNP), and literacy rate. However, certain important ingredients of the quality of life can’t be measured, like the degree of self-determination people have, or how much beauty there is in their lives. Moreover GNP can be very misleading as an indicator of the quality-of-life. It includes products harmful to the environment, such as armaments, toxics, or wood from clear-cut forests. It is ironic that GNP includes both cigarettes and medical costs of treating respiratory diseases made worse by cigarettes (and air pollution).

Unless countries like China, India, and yes, the United States can control their population growth and the attendant environmental problems, the future quality of life for all of their citizens is in jeopardy. Together India and China have almost 38% of the world’s population. What happens to them and what they do is sure to affect the entire world.

PG8.1. Investigation:

The Quality of Your Life

Meet with a small group of people (e.g. classmates) and decide what items your group would put on a quality-of-life list. Your group might select items such as personal health, economic security, political freedom, companionship, high level of education, and others. Work with your group to put the list in order of priority. If the population doubled, decide among yourselves which of the items on your list would be affected. Describe what might happen. Which of the items on your list can be measured? For those that can’t be measured easily can your group suggest a method of measuring them? Have a reporter in your group keep the list with notes on your decisions. After your group work is complete compare your results with those of the rest of the class. Can the class establish a list that all can agree on?

Interview your parents or any two adults and help them to establish a quality-of-life list of their own.

How is the list produced by your interview with adults similar to the list created by your class? How is it different?

Compare a simple fisherman with a hand net to a giant Japanese trawler with miles of drift nets. It is a common story. A single man with the inventions and techniques of an industrialized civilization can have a greater impact on the environment than hundreds of individuals who live in a nonindustrialized way.

The same technological innovations that have, for many people, made life longer and richer than at any previous time in human history have done so at a cost. The cost is the impact on the environment.

IV. Where Do We Go From Here?

Henry David Thoreau, the American philosopher of nature wrote, in the late 1800s, “What is the value of building a home, if one does not have a decent planet to put it on?”

In this book we have seen how human population growth can cause global environmental problems. The next question is, “What are we going to do about it?” It’s tempting to think that the problems are so large, there is nothing that we, as individuals, can do. It’s easy to say that they should have fewer children. Or that they, the rich people of the world, should not squander raw materials and energy in wasteful ways.

Compared to most of the rest of the world, Americans’ way of life is a wasteful one. No matter how small, every reduction in our demand on the Earth’s resources helps. If we multiply the contribution to save energy, buy less and recycle more, by each and every person living in the U.S., there will be a real reduction in global environmental impact.

We can also think about technology in a different way. The idea of using appropriate or small scale technology is not restricted to developing countries. Our electrical power systems consist of

- centralized generating plants burning coal or oil, putting smoke and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere,

- towers supporting high voltage electric lines across the countryside interrupting the beauty of the landscape,

- intermediate power stations to distribute this electricity,

- massive networks of wires to each home and business.

Much of the energy is lost to heat as it moves through wires. What if small solar or wind-powered generators could provide the electricity needed at many locations? Those clean, sustainable energy technologies were not available when communities were first electrified.

Many environmentalists fear that exporting technology to developing countries will increase the industrial impact on the global environment. But technology is not automatically detrimental to the environment. It depends on what the technology is and how it is used. For example, a few years ago, in an effort to increase the flow of water for drinking and irrigation of crops in Kenya, relief organizations shipped gasoline powered pumps costing several thousands of dollars each to rural villages. Not only did the pumps require expensive gasoline but when they broke down there were no technicians to repair them. It was only when local workers were shown how to build efficient foot-operated water pumps costing about $100 each that these villages truly benefited.

Finding fuel for cooking is a major issue in many developing countries where wood and even dung has become scarce. A movement to use simple, inexpensive solar cookers has proven to be a clean, sustainable solution to this problem in many areas. Check Solar Cookers International web site [http://solarcooking.org/] to find out more about this movement.

- If we believe that all people are created with an equal right to live life fully, then a sustainable world must include an increase in the level of prosperity and security for everyone, both in our country and in the less developed nations of the world.

- Future generations of men and women also have the right to live as fully and as richly as we do. They will need a share of the resources of the Earth. Consideration of the needs of future generations must be part of sustainability.

- Sustainability has to include the idea that economic growth and resource development must be limited by what the global environment can support on a continuous basis.

People today who take these ideas seriously and who work to spread this new attitude among their friends and neighbors, who encourage appropriate legislation, and who endeavor to live more lightly on the Earth, are a new kind of world citizen.

The Earth will endure in one form or another no matter what we do to it. The question is, now that we have the power to change the global environment, what kind if Earth do we want to live on?

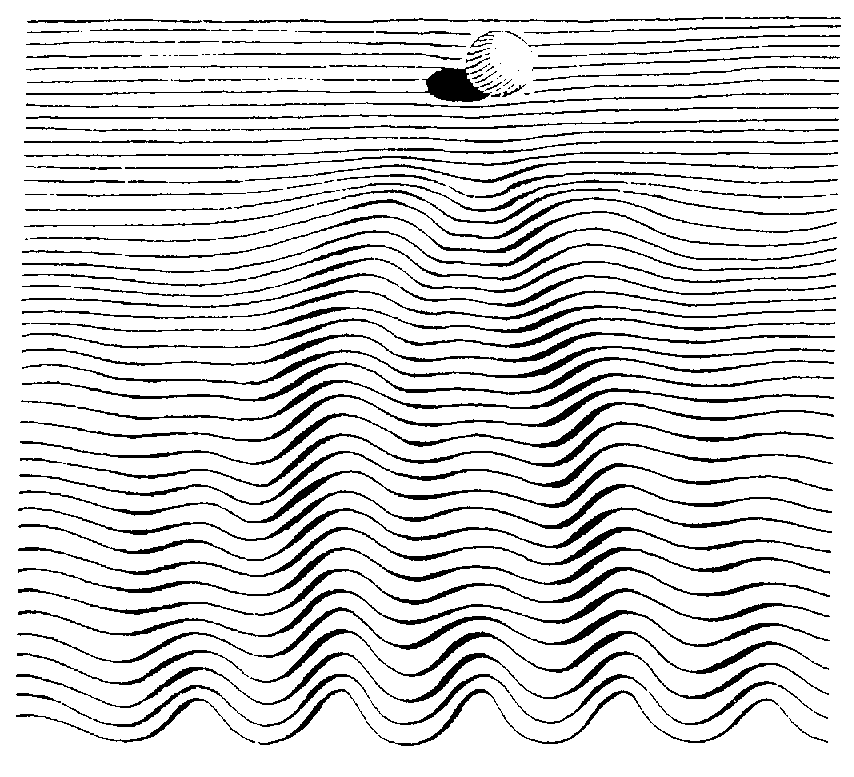

It does not necessarily take a great many people to change the course of human history. Consider a ball rolling down a slope. The slope has ridges and valleys running downhill. If a small sideways push is applied to the ball its rolling course is altered and it rolls down into a completely different valley than the one it was headed for.

The ball is human history. The valleys are alternate futures. A relatively small number of people can provide the sideways push to get the ball rolling in a different direction. The decisions each of us make, both large and small, and the values we choose to pass on will determine the future of life on Earth.

V. A Sustainable World

During most of human history, our species has survived by cooperation, developing ways of life that were sustainable over the long term. But recently, both human population growth and a high consumption life style have become unsustainable in the long run. There is a need for us to examine our activities and, where they cannot be sustained in the long run, decide how to modify them. There is also an ethical problem for the people of the industrial countries if part of their life style is supported by the impoverishment of people in the underdeveloped countries. Is your clothing put together in sweatshops located in Asian nations? These sweatshops employ young children and are run by American corporations.

PG8.2. Investigation: The Road Not Taken

The decisions each of us make, both large and small, and the values we choose to pass on will determine the future of life on Earth.

Read the following poem by Robert Frost. How does the poem relate to the picture of the ball rolling on a wavy surface? Can you relate the poem to decisions your generation may be making about the kind of world you want for yourself and for your descendents?

The Road Not Taken

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

–Robert Frost (1874 – 1963)

Make a list of the ways humans are affecting Earth systems that seem important to you. (Humans are affecting the atmosphere by …… Humans are affecting the land by …… Humans are affecting the oceans by ….. Humans are affecting ecosystems by ……)

Write down how you think you and your actions relate to each of those impacts.

For each of the interconnections between you and the impact on Earth systems state why you are satisfied or dissatisfied with your actions.

Question 8.2.

If you had the power to change how humans, in general, relate to the Earth, what changes would you propose?

Question 8.3.

What suggestions would you make so that the quality of life for all people in the world could be improved?

VI. The Earth Charter Initiative

The Earth Charter Initiative began in 1987, when the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development issued a call for creation of a new charter that would set forth fundamental principles for sustainability based on respect for nature, universal human rights, economic justice, and a culture of peace. These principles are also based upon contemporary science, international law, and the insights of philosophy and religion.

The preamble of the Earth Charter is as follows

We stand at a critical moment in Earth’s history, a time when humanity must choose its future. As the world becomes increasingly interdependent and fragile, the future at once holds great peril and great promise. To move forward we must recognize that in the midst of a magnificent diversity of cultures and life forms we are one human family and one Earth community with a common destiny. We must join together to bring forth a sustainable global society founded on respect for nature, universal human rights, economic justice, and a culture of peace. Towards this end, it is imperative that we, the peoples of Earth, declare our responsibility to one another, to the greater community of life, and to future generations.