LB8. Champions of a Sustainable World

Chapter 8

{ Losing Biodiversity Contents }

“We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

– Aldo Leopold, 1948

Visit Yellowstone today, and despite roads and tourists everywhere, you may still feel the awe of Nature which moved people to help make this the first National Park in 1872. The history of the conservation movement in the United States is woven from thousands of individual stories. Each one was inspired by Earth’s wonderful environments and variety of life.

The recipe for successful conservation efforts often goes like this:

A person discovers a problem that she or he cares very deeply about. The person shares the concern with others, often gaining encouragement from friends and family. Working together the “grassroots” group develops a plan for how to spread the word to the community and to law makers.

In this chapter, we continue to describe a few of the many stories of how people have made a difference in saving species and environments. A Losing Biodiversity Timeline at the end of this chapter highlights some of the most important conservation successes and environmental catastrophes of the past two hundred years.

I. What Is Conservation?

The word “conserve” means to save. We conserve energy by turning off lights when we leave the room. We conserve water by turning off the faucet when we brush our teeth. Gifford Pinchot invented the term “conservation” in 1906. At that time he was working under President Teddy Roosevelt and urging Congress to set aside national forests to provide a lasting resource for the future. His motto was “A resource should be used to provide the most good for the most people for the longest time.”

Today the word “conservation” has evolved to mean “sustaining natural resources for future generations.”

Conservation Perspectives.

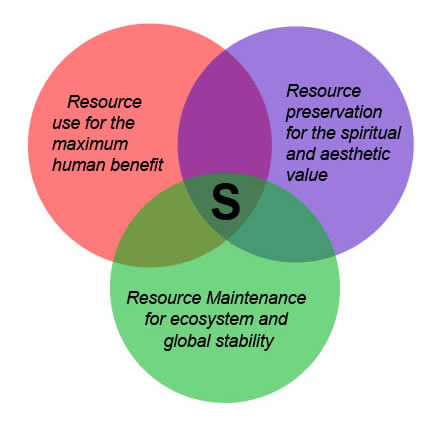

The “S” in the center represents the

common goal of sustainability

People with widely differing viewpoints consider themselves conservationists. Some want to save nature for its spiritual and aesthetic value. These people are often referred to as “preservationists.” John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club and champion of the preservationist movement, wrote articles and led citizen campaigns resulting in Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks.

Some people want to use nature for its benefits to humankind. Still others have an interest in sustaining ecosystems for their value to the global system. The following diagram is one way to show how conservationists may differ or agree on various environmental issues.

II. Who Can Be A Conservationist?

Anyone and everyone who helps sustain Earth’s resources can be a conservationist. News reporters have traditionally been the first to alert the public to environmental problems discovered by scientists and observant citizens. The journalists who traveled west in the 1800’s stirred people into action with their vivid descriptions and drawings of the bison slaughter.

Movies and television have vastly expanded the educational impact of the news profession by enabling the average citizen to see what is going on in environments around the world. Reporters can present the reality of oil spills, forest clear cuts, and slaughter of animals such as whales to millions of TV viewers in a single evening.

Students and teachers from schools and colleges have often helped spread information from the news media to their families and neighbors. In the case of the Tuna Boycott, school children around the country made presentations in their communities describing the fishing practices that were killing dolphins along with the tuna.

Scientists are providing evidence of the importance of sustaining species and environments over the long term:

- Population studies of species such as tuna, bison, and redwoods, reveal ways to ensure sustained production for future generations.

- Soil studies show how to maintain the long-term fertility of the land.

- Atmospheric research reveals the importance of forests, marshes, and ocean plankton in removing CO2 from the air.

- Plant ecology experiments reveal the relationships between various species and the effects of diversity on plant productivity.

- Biochemistry research into Nature’s “chemical factory” of living things enables the discovery and production of new drugs and manufactured goods.

- Physiology research into the effects of toxic chemicals such as DDT, PCP and dioxin has guided law-making to protect people and wildlife from pollution and pesticides.

III. Economic Value of Nature

More than a century ago, George Perkins Marsh was one of the first Americans to speak out about the waste of natural resources. Marsh wasn’t a scientist, but a self-taught Vermont lawyer. While traveling in Europe and America Marsh noticed the results of widespread forest clearing and erosion of soil. “Every middle-aged man who revisits his birth-place after a few years of absence, looks upon another landscape than that which formed the theatre of his youthful toils and pleasures,” he observed.

create an urban garden in San Francisco

Dismayed by the ruin of the land, Marsh set out to document how people were upsetting the balance of nature to their own detriment. He made the case that the variety of life in wild forests had economic value. He pointed to deforestation as a cause of the decline of Mediterranean empires. In his book Man and Nature, published in 1864, Marsh set out the principles of resource management and sustained productivity that stimulated the conservation movement.

At the same time that Marsh was developing his view of wise use of the land, philosophers like Henry David Thoreau were voicing a spiritual view of nature that came to be known as Transcendentalism. “I wish to speak a word for Nature, for absolute freedom and wildness. …in Wildness is the preservation of the World.” Thoreau wrote in 1851. Poet Ralph Waldo Emerson was another eloquent spokesperson for Earth’s treasures—“Nature is the symbol of the spirit” (1836).

Environmental ethics are not new. Many cultures have strong beliefs about being caretakers of the land and wildlife. European cultures, however, were generally driven by expansionist goals to seek new resources elsewhere when forests, wildlife, and farmlands were depleted at home. Voices like Henry David Thoreau, Alfred Russel Wallace and John Muir, were champions of the idea that the wonders of Nature should be protected for their spiritual and aesthetic values.

Even before the voices of these early conservationists, Native Americans upheld an ethic of land stewardship. As one writer about Native American culture pointed out: “Owning the land, selling the land, seemed ideas as foreign as owning or selling the clouds or the wind.” (Kirpatric Sale, Conquest of Paradise pg. 314) This view of land stewardship was in sharp contrast to the utilitarian view of nature held by the majority of settlers who flocked to the “New World.”

The evolution of environmental ethics as a legal concept is beginning to provide a basis for protecting species and environments, even ones that may have no immediate monetary value. Does a species have the right to exist? If so, how might we legally recognize that right? Do future generations have environmental rights? If so, what legal guidelines should we have for people today to make sure they sustain resources for the future? How might we measure the value of a unique landscape or an unusual creature? These are a few of the ethical questions that are becoming more and more important as humans transform the planet at an ever-increasing rate.

IV. Why Save Old Growth Forests?

The creation of parks and reserves has almost always involved a struggle between land developers and citizens claiming benefits for the nation and future generations. In the years just before World War II, conservationist Rosalie Edge led the battle to create Olympic National Park around the last major old growth redwood forest in Washington State. Most of the State’s political leaders, journalists, and citizens rallied behind the timber industry’s claims that the proposed park would destroy the region’s economy. The country was just beginning to recover from the Great Depression, so the prospect of losing jobs and 22 billion feet of timber was alarming to most people. There were already a lot of parks, why did we need another one?

Rosalie Edge formed a team with scientist Willard VonNam, and journalist Irving Brant to educate members of Congress and citizens throughout the country about the aesthetic and biological importance of this special northern rain forest. They distributed a carefully researched plan with maps and photographs of the unique forest. When Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Congressional bill in 1938 establishing Olympic National Park, it was a milestone in acknowledging the value of old growth forest habitats.

V. Why Save Desert Habitats?

The 1994 passage of the Mojave and Death Valley Deserts National Park Bill is another example of a battle that took many years. Mining companies, cattle and sheep grazers, and off-road vehicle groups successfully stalled the legislation year after year. “There are already a lot of parks, why do we need another one?” people asked. “Parks are expensive; why use money on barren deserts that could go to the other parks?”

Perhaps because deserts seem inhospitable places, scientists and conservationists have had a difficult time educating us about these very special ecosystems. In fact, deserts are rich in species diversity, supporting plants and animals that are uniquely adapted to surviving the harshest conditions. Peter Burk and his wife Joyce, both librarians from the desert town of Barstow, fell in love with the desert wildlands during their daily hikes. Their grassroots efforts to save this fragile ecosystem began in 1976 with spaghetti dinners and T-shirt sales to promote desert protection.

Elden Hughes, a private citizen, devoted years to educating politicians and the general public about desert wildlife. He brought gentle tortoises to the halls of Congress to help people experience first-hand the amazing adaptations of desert evolution. There are many other individuals who worked to preserve the unique species and habitats of this isolated region. Senator Diane Feinstein’s and the late Senator Alan Cranston’s names have been linked to the desert park movement because of their perseverance in getting the bill through the Senate.

VI. Does A Species Have A Right to Exist?

The 1973 Endangered Species Act cast a spotlight on the issue of biodiversity. It has been described as a safety net for species such as the bald eagle and the whooping crane that were “falling through the cracks” of our nation’s resource management systems. The controversies and political decisions stimulated by this Act have helped to educate the American public about the importance of protecting biodiversity.

This landmark legislation supported and signed by President Richard Nixon reads in part:

“The Congress finds and declares that various species of fish, wildlife, and plants in the United States have been rendered extinct as a consequence of economic growth and development untempered by adequate concern and conservation…. These species… are of esthetic, ecological, educational, historical, recreational, and scientific value to the Nation and its people… The purposes of this Act are to provide a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved…”

The Act prohibits federal agencies from “funding, authorizing, or executing” any action that would jeopardize or destroy or modify areas designated as its “critical habitat.” The Act also requires the agencies overseeing its enforcement, which are generally the National Marine Fisheries Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, to draw up recovery plans for listed species. These may include purchase and management of land as well as captive breeding programs.

Why is the Endangered Species Act considered a cornerstone of efforts to protect biodiversity? It was the first national legislation to recognize that species have aesthetic, recreational, and scientific values in addition to the more commonly recognized commercial values. This distinction has been particularly important for protecting plants and animals that are small and little studied.

An important feature of the Act has to do with the decision of whether a species should be listed as endangered. The Secretary of the Interior may consider only whether the species is endangered or threatened, not whether it would be too costly or inconvenient to protect. This key point recognizes a species’ legal right to protection if it is designated as “endangered.”

VII. The Case of the Black-Footed Ferret

The frisky little black-footed ferret may be rescued from the brink of extinction as a result of years of scientific research and the funding and the protection it received through the Endangered Species Act. Its survival depends on a combination of captive breeding programs and changes in range land practices.

The ferrets were once an important predator of the Great Plains ecosystem, feeding almost exclusively on prairie dogs.

Following World War II, ranchers began an eradication campaign against coyotes and prairie dogs. Coyotes killed farm animals such as chickens and lambs, while prairie dogs competed for grass with the livestock. The landowners used a new weapon, “1080”, an extremely toxic, odorless poison developed by the Nazis for chemical warfare. For decades, ranchers used 1080 across the western plains causing the decline of many wildlife species that ate the poisoned grain and meat bait. Populations of golden eagles, owls, foxes, skunks, and other mammals were greatly reduced along with the near extermination of the prairie dog.

Black-footed ferrets eat prairie dogs and use their burrows for dens and to hide from bigger predators. Along with coyotes, bobcats, and eagles, they undoubtedly helped to regulate prairie dog populations. So, by using 1080, the farmers destroyed not only prairie dogs but their natural predators as well.

The “Black-footed Ferret Endangered Species Program” began with about a dozen ferrets, so the genetic diversity of the breeding colony was very small. As we saw in previous chapters, variation in genetic traits provides a species with built-in insurance against changes in the environment. To guard against diseases like distemper that could wipe out the entire population, biologists have been very careful to establish breeding colonies in a number of laboratories.

Fish and Game Departments in Wyoming and Montana and the Fish and Wildlife Service have invested millions of dollars in breeding and research studies to save this unusual and lovely ferret. Their success will also depend on the responses of local ranchers, community members, and politicians, in maintaining a climate of support over many years. Black-footed ferrets are now being released into the wild and time will tell if the species will overcome difficult biological and political odds.

Note: The use of 1080 for predator control was banned in 1972, but some states continued until recently to use it for rodent control. Countries like Australia still use 1080 to control rabbit, fox, and dingo populations.

VIII. Toxins in the Food Web

Following the publishing of Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring in 1962 DDT and eleven other chemical pesticides Carson warned about were banned or tightly restricted. Extensive laboratory and field research has revealed how DDT affects organisms, and how it is transported through the food web of ecosystems to cause declines in wildlife populations.

For example, biologists are finding that peregrine falcons, brown pelicans, and many migratory birds in California are still accumulating DDT twenty years after it was banned. DDT is still manufactured by foreign subsidiaries of U.S. companies, and other countries continue to spray vast wetland areas for mosquito control. Several U.S. government agencies are now in litigation to stop production of DDT by the Montrose Chemical Corporation, the largest manufacturer of DDT in the world.

Rachel Carson predicted that people would eventually exhibit the effects of DDT, and recent studies of breast cancer in women and prostate cancer in men have shown high levels of DDE in the fatty tissues of these cancer victims. A tragic irony is that Dr. Carson died of cancer in 1964 before witnessing the successful efforts to finally ban DDT in the U.S. in 1972. Her very popular book stimulated wildlife and human research that continues today.

The spotlight that Rachel Carson put on environmental pollution has resulted in success stories like that of the bald eagle. In 1963 there were only 147 breeding pairs of bald eagles in the lower forty-eight States.

The banning of DDT, combined with captive breeding and research programs made possible by the Endangered Species Act has enabled the eagles to bounce back from the brink of extinction. Today there are an estimated 4,000 breeding pairs of bald eagles south of Canada, and the birds have been down-listed from endangered to threatened status.

The U.S Environmental Protection agency has lot of information on toxic chemicals, health hazards, and environmental hazards, for example:

IX. How Can We Protect Habitats?

Another crucial part of the Endangered Species Act is the legal recognition of the need to protect critical habitats. All species are part of a natural community of interacting plants, animals, fungi, bacteria, and other microorganisms. Conserving natural habitats provides the basis for long-term protection of entire communities of species.

Up to this time, the most effective way to protect critical habitats has been to create parks and reserves. As we have seen earlier, beginning with the protection of Yellowstone in 1872, the U.S. has provided an important model for the world by establishing an extensive system of national parks, wildlife refuges, national reserves and sanctuaries.

Did you know that less than ten percent of the U.S. is protected in parks and reserves? These relatively small and isolated environments are not enough to ensure the survival of a reasonable representation of North American species.

If school yards, backyards, farms, range lands, industrial parks, highway corridors and other plots of open land become havens for native species and are managed to promote species diversity, the prospects for wildlife would be brighter.

Ecologists have shown us that we can bring back species from the brink of extinction and restore environments. This powerful message is being acted upon by millions of citizens around the world. Let’s look at some specific ways that people have restored environments in their own backyards.

Adopt A Species

In 1992, Lorette Rogers and her fifth grade class at Brookfield elementary school decided they wanted to help save an endangered species. The class had just learned about the Audubon Society’s Adopt A Species Program, which encourages school groups in California to help a local plant or animal that is threatened. After finding out about all of the endangered species in their area, the Brookfield students chose a very unusual and little-known animal—the California fresh water shrimp.

Students read scientific reports and interviewed biologists to find out that grazing was a major cause of the problem. Cattle feeding along stream banks had destroyed the shrubs and grasses that provided shelter and shade, and cow droppings had polluted the water. Erosion of soil along the stream banks caused muddy water which also affected shrimp reproduction. With advice from biologists, the students identified a region of a stream that might have some surviving shrimp that could benefit from a restoration project.

The students agreed that confronting the local land owner could create hard feelings and decrease their chances of success. The farmer was having a hard time making a living from the land and might refuse to work with them. To develop cooperative strategies for working with private citizens and groups, the students completed a training program on techniques for productive communication. This helped them have more appreciation for the different viewpoints within their community.

The students conducted water tests, cleaned trash and old junk out of the stream, replanted areas of the stream banks with plants, and conducted awareness campaigns in their school and community. They were so successful in working with the dairyman who owned the cows, and in getting donations of native plants to restore the stream vegetation, that they won a national conservation award of $30,000 from the Anheuser Busch Foundation. The students went on to recruit other classes and volunteers to their project.

Adopt an Urban Habitat

Chances are you live in a city—three out of every four Americans do! Between 1950, and 1990 the number of people living in cities rose tenfold from 200 million to over two billion. We have become an urban species living with pollution all around us. Thousands of students around the country have chosen to help change their communities to be healthier places for people and nature.

The problems of cities are well-known. People can lose touch with their families and community. In a city it is easy to go to school or work and back each day without talking with or even saying “hello” to other people who live nearby.

On the other hand, cities bring together a richness of cultures, ideas, and enterprise that can make our country more productive. Cities have always been a lure for young people for all of the choices they offer. The often grim conditions of cities have inspired great examples of problem solving from all sectors of society. Urban environments have become part of our humanity, and have fostered the social evolution of cooperation among cultures.

A growing number of Americans are realizing that efforts to improve the ecological environment of cities must also address the civil rights issues that link environmental and social justice issues. For example, in many poor urban neighborhoods, industrial pollution goes unregulated and the government is slow to require the clean-up of toxic waste dumps. The term “environmental justice” is being used for the grass roots actions of local citizens working to improve the environmental health of their living and working conditions.

According to a 1987 study by the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice, “Three out of every five black and Hispanic Americans live in communities with uncontrolled toxic waste sites.” In Chicago, nearly two-thirds of the city’s 162 federally designated toxic “hot spots” are in neighborhoods where predominately people of color live.

Hazel Johnson, mother of seven children and an African American, received the 1991 President’s Environment and Conservation Challenge medal for her work in improving the environmental health conditions of a Chicago housing project surrounded by industry, landfills, and incinerators. She founded People for Community Recovery, a nonprofit group that has convinced Chicago officials to place a moratorium on new waste dumps and incinerators in the area and to begin to monitor and regulate local air quality.

The Urban Habitat Program is an example of a San Francisco group that is working to bring the urban poor together with environmental organizations to solve inner city problems. By linking economic and social justice issues to related environmental problems, this group gets minority communities involved in local environmental and economic restoration. A few of the issues being tackled through the legal system by community groups working for environmental justice include:

- clean-up of toxic waste dumps near neighborhoods,

- protection from toxic chemicals in the workplace,

- creation of urban parks,

- access to safe drinking water,

- improvements to local schools,

- better access to public transportation, and

- removal of lead contamination in buildings.

Adopt A Garden

As you read this, thousands of acres are being covered with parking lots and contaminated with chemicals. At the same time, thousands of city people are reclaiming small plots of soil and bringing gardens and wildlife back to the urban expanses of concrete and freeways.

In San Francisco, one hundred community gardens have been created on what were once neglected plots of private or public land. These neighborhood gardens have brought together people from many cultures with the common purpose of producing food and flowers where none grew before.

The idea for community gardens is not new, and examples can be found in many towns and cities. The San Francisco League of Urban Gardeners, known fondly as SLUG, began its educational campaign in 1983. This multicultural group has demonstrated that the benefits of urban gardening go far beyond the small pieces of land that get transformed. People come together and learn from each other, gaining new ideas and skills that they pass along to new members.

SLUG staff teach the techniques of composting, organic gardening, and basic horticulture in their “Garden for the Environment.” All of the food grown in the garden is donated to homeless shelters. The steep parts of the garden are planted with native species to provide a habitat for wildlife. Teenagers sentenced to community service can choose to help SLUG build and maintain community gardens. Students can eventually get paid for their work while they learn valuable job skills and are put in touch with the weather, the seasons, and the beauty of nature.

Adopt the Planet

Across the world there are examples of people working together to reduce our collective impact on the environment. Clinton Hill was a sixth grader who in 1988, started a group called Kids for Saving Earth (KSE). Clinton died of cancer, but his determination to make a difference in protecting the environment stimulated other students to join the effort. The non-profit group now has more than 10,000 KSE clubs in North America and more than 400,000 student members worldwide who are working to conserve natural resources.

The KSE Worldwide web site features action projects for students and has links to environmental education resources: http://kidsforsavingearth.org/

Kids For Saving the Earth Promise:

The Earth is my home.

I promise to keep it healthy and beautiful.

I will love the land, the air, the water and all living creatures.

I will be a defender of the planet.

United with friends, I will save the Earth.

X. A Global Conservation Strategy

During the writing of this book, congressional subcommittees of the Senate and House of Representatives were changing key provisions of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) to weaken its protection of organisms and habitats. Congress was also cutting funds to wildlife research and to the National Fish and Wildlife Service, which enforces the ESA.

Many wonder if the ESA, a milestone in environmental ethics legislation, will survive a political process that is often driven by economic considerations. It may seem very sensible to establish regulations for conserving plant and animal populations so that they may renew themselves year after year. Unfortunately, the immediate well-being of a select group of people often comes into conflict with preservation of the last habitat of an endangered species.

It may be easier for the U.S. Congress to weaken the Endangered Species Act, than to develop alternatives for helping people find new means of support. Whatever the fate of the Endangered Species Act, its impact has already been felt worldwide, as other countries have developed environmental policies incorporating U.S. models. The 1993 Convention on Biological Diversity, signed by 170 nations, marked an unprecedented worldwide commitment to stem the loss of the earth’s species, habitats and ecosystems.

The Convention called for countries to establish national parks and protected areas, promote recovery and rehabilitation of threatened species, expand research and public education, and utilize environmental impact assessments. A second major goal of the Convention was to promote the sustainable use of biodiversity. By emphasizing measures to realize the economic and other benefits of biodiversity in a sustainable manner, the Convention encourages countries to conserve their biodiversity.

Humans are a resilient species and we do learn and teach others quickly. This capability to communicate and cooperate may be our greatest tool in sustaining our planet’s rich resources. As we examine the history of how people have changed the face of the Earth, we find the recurring forces of population growth, technology, and uncontrolled competition for Earth’s rich but limited resources. By taking a global view of this pattern of loss, we can begin to understand the urgency of global conservation. We encourage you to look for ways that you might help maintain Earth’s biodiversity.

LB8.1. Investigation: Final Essay

Write an essay about a key issue or event that has affected biodiversity. The Biodiversity Timeline at the end of this chapter may give you ideas for a topic. The essay should be written according to the format and length requirements set by your teacher. In preparing for your essay, please do the following:

- Research the issue, using the Internet, local scientists, and your library. The list of conservation organizations at the end of the chapter can also provide ideas.

- Draft a short statement of the event or controversy, then draw a line down the center of a sheet of paper. On the left, list the most important points that were made by conservationists. On the right, list opposing arguments held by other citizens, industry or government agencies.

- Decide what actions would be consistent with your position regarding the controversy.

- Make an outline of your essay. Decide on the order in which to present your points on both sides of the issue. Give your own opinion and support it with logical arguments and information. End the essay by saying what actions you and others might take (or not take) that are consistent with your opinions on this subject. Choose a title that captures your most important idea or conclusion. Make a list of references that you used.

- Share your outline with your classmates. Find out what they think, and discuss the points where you agree and where you differ. Modify the outline based on new information or ideas.

- Write an essay. If, in some way, you have called for action, consider what specific steps should be taken to achieve the result you are calling for. Identify actions which you could initiate, then undertake those actions yourself!

- Share your essay with other groups of people. For example, send a copy to a conservation magazine like National Wildlife, a community paper, or your school paper.

Conservation Organizations

- List of conservation organisations – Wikipedia

- Center for Biological Diversity – http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/

- Conservation International

- International Anti-Poaching Foundation – https://www.iapf.org

- Jane Goodall Institute

- National Audubon Society

- National Wildlife Foundation – https://www.nwf.org/

- Natural Resources Defense Council

- Oceana

- Orangutan Foundation International – http://www.orangutan.org/

- Sea Turtles – http://www.scistp.org/

- Tiger information center – 5 Tigers http://www.5tigers.org/

- World Wildlife Fund – https://www.worldwildlife.org

See Staying current for this chapter.

Biodiversity Timeline

Can you make a Timeline that brings this series up to date?