LB2. The Trail Back From Near Extinction

Chapter 2

{ Losing Biodiversity Contents }

Imagine you are sitting on a hill looking out over prairie grassland that stretches as far as your eyes can see.

The time is the spring of 1492, and you, an Omaha Indian, eagerly await the return of the buffalo. On the southern horizon, a black tide moves steadily towards you. With great excitement, you run to bring the good news to your people—buffalo have come back to the green grass of the north, bringing their calves to better pastures!

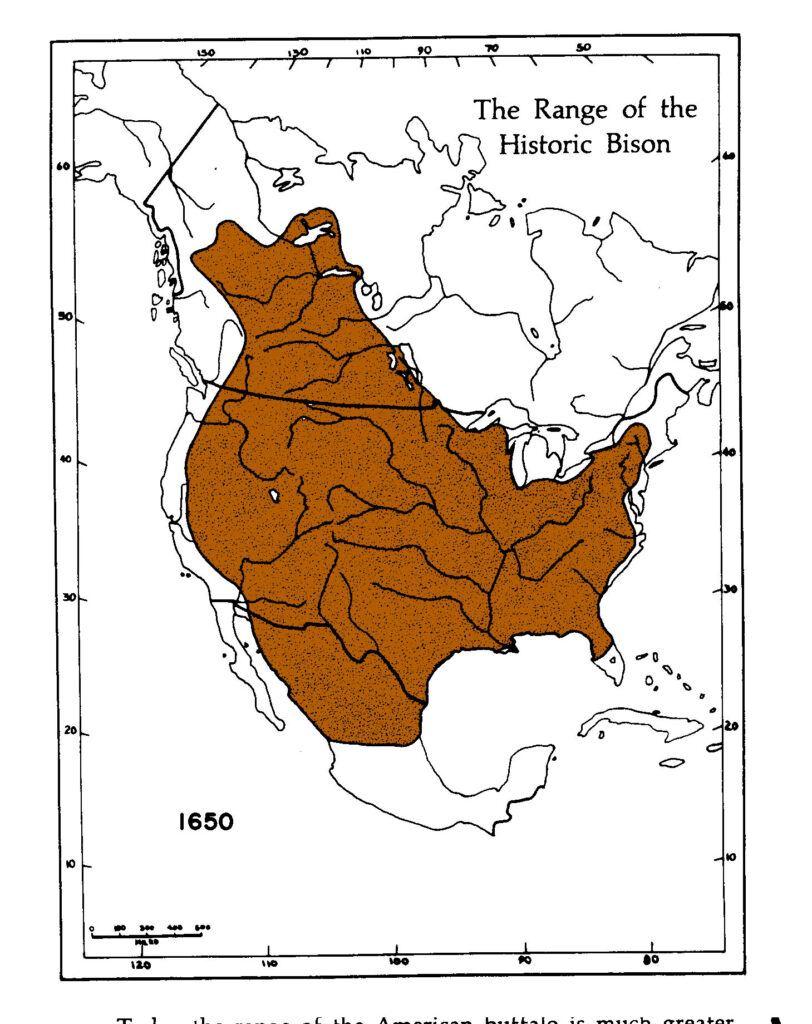

Five hundred years ago, vast herds of buffalo ranged from the Appalachian Mountains to the Rockies, and from central Mexico northward to the Arctic. European explorers told of limitless grassy plains blanketed by the large shaggy beasts, known in scientific terms as Bison bison.

By 1850, the great herds had dwindled to an estimated twenty million animals. Even then, trains were often stopped for long periods while migrating herds crossed the tracks. By 1888, only 1300 bison were left, and their numbers continued to decline. Not only had the buffalo declined, but the daily routines of the Native American tribes, who had depended on the buffalo, had also suffered. Deprived of their primary source of food and clothing, small clusters of survivors struggled to exist on government reservations.

If we could return to the Great Plains of the 1500’s, we would find an abundance of animals and plants that today survive only in small islands of natural habitat—bison, pronghorn, elk, wolves, grizzly bear, prairie dogs, eagles, black footed ferrets, and more than 600 species of grasses and other plants. The prairie soils for the most part would be rich and deep, protected by a thick sod of perennial grasses and plants like clover. Today we find less biodiversity and less fertile soil throughout the region.

I. Bison—A Keystone Species

Because the bison affected the plants and wildlife across a million square miles of country, it was what biologists now call a “keystone species.” A keystone species is a kind of organism that dominates a region, providing food, habitat, and special circumstances for other kinds of organisms that rely on it to maintain the natural community.

Redwood trees are an example of a keystone species of the coastal mountains of Northern California. The forests support communities of plants and animals that cannot survive without the redwoods. The giant brown algae that forms the kelp forests off the California coast is another example of a keystone species. These ocean “forests” provide food and shelter for many marine organisms.

A bull buffalo guards his herd.

From Animals, Jim Harter. 1979, Dover Publications

The bison were the dominant large animal on the Great Plains following the retreat of the glaciers around 12,000 years ago. Thick shaggy coats protected them from cold as well as predators. Their powerful shoulders were adapted for plowing through heavy snow to reach food. Other grazing animals benefited from the snow corridors opened up by the powerful bison. Bands of pronghorn mingled with the bison herds and packs of wolves followed the migrations. The wolf and the plains grizzly bear ate the less aggressive animals, the lone wanderers, and the sick.

Based on the few observations of early explorers, biologists speculate that each herd migrated in a roughly circular route that covered a thousand or more miles. The pattern and timing of bison movements enabled the regrowth of the depleted grasslands left in their wakes. The bison shared the prairies with great flocks of prairie chickens, plovers, and curlews. Prairie dogs, small squirrel-like rodents, benefited from the grazing herds, which ate the grass and improved the rodent’s view of lurking predators such as foxes, coyotes, hawks, owls, eagles, and ferrets.

The annual rhythm of grazing and migration, together with wild fires and drought, inhibited trees from invading the grasslands. The cycle of grazing and migration promoted hardy species of grasses and other plants with extensive root systems.

The bison were a keystone species for Native American cultures as well. Every part of the animal was put to some use, and its value was acknowledged through art, language, religion and tradition. The woolly capes were blankets and robes, the various kinds of tanned hides became ropes, moccasins, teepees, boats and shields. The hollow horns were made into cups and ornaments; the bones were fashioned into fishhooks, tent pegs and clubs; the hooves provided glue. Dried buffalo dung was the principal source of cooking fuel on the prairie.

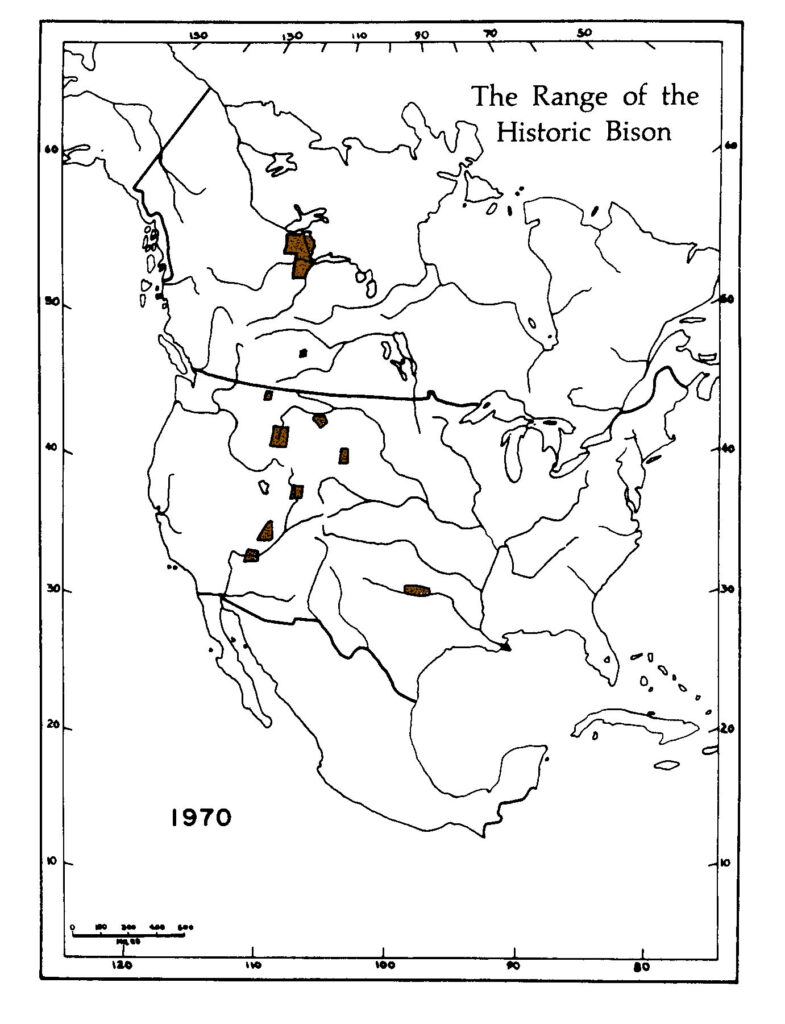

Maps below show the estimated distribution of bison in 1960 and in 1970.

From The American Buffalo in Transition, J. Albert Rorabacher.

~~~

LB2.1. Investigation:

Estimate the Number of Bison Killed

Buffalo skulls that were shipped from Saskatoon to Minneapolis, Minnesota, to be made into bone charcol. The skulls are stacked eight feet high and eight feet wide by 200 feet long!

From The American Buffalo in Transition, J. Albert Rorabacher 1970.

Bison bones were used as a refining agent in sugar processing, for fertilizer, bone charcoal, and for fine bone china. Records of railroad shipments of bones into Kansas City reveal the following information:

- From 1868 to 1881, $3,000,000 were paid for bison bones.

- A ton of bones sold for an average of $8.00.

- It took 100 buffalo skeletons to make a ton of bones.

Question 2.1.

How many bison were killed over the 13-year period?

Question 2.2.

What was the average number of bison killed per year?

Question 2.3.

Kansas City was the major center for railroad shipments East, but there were other smaller trade routes to the north and along the rivers. How does the number of bison estimated above relate to the total number that were actually killed?

II. What Happened To the Buffalo?

The human population of the United States doubled between 1840 and the end of the Civil War in 1864. The California Gold Rush in 1848, the Homestead Act of 1862, and the building of the transcontinental railroad combined to bring a flood of settlers and market hunters westward.

At that time, there were no laws protecting wildlife from commercial hunting.

Along the eastern Coast of the United States, market hunting had already led to the extinction of the Labrador Duck, Heath Hen, and Great Auk. Citizens were beginning to push for laws to regulate the harvest of game animals. The idea that people should be stewards or caretakers of the land and wildlife was beginning to spread among educated professionals who had the time and money to enjoy nature and sport hunting. This concept of stewardship was in its infancy, however, and the drive to develop new lands far outstripped the new ethics of conservation.

In the summer of 1843, artist John J. Audubon traveled 1500 miles up the Missouri River to paint western wildlife. He noticed that buffalo were much less abundant than reported by earlier explorers like Meriwether Lewis. “Before many years,” Audubon warned, “the Buffalo, like the Great Auk, will have disappeared; surely this should not be permitted.”

In 1865, the estimated annual bison kill was a million animals. With the arrival of the railroads on the prairies, the annual kill climbed steadily each year to a crest of nearly five million in 1872. A good day’s work for a competent hunter was 40 to 60 bison. The long-range Sharps rifle could drop a bison at a thousand yards. William F. Cody, popularly known as “Buffalo Bill,” claimed he killed 4,280 buffalo in 18 months.

After 1873, only scattered bands remained south of the Platte River, too few to support commercial hunting, although cowboys, settlers, and prospectors shot the survivors whenever they could. In less than eight years, nearly all of the tens of millions of buffalo that had roamed the prairies of Arizona, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, Wyoming, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah had been converted to hides, bones, and for the most part, rotting carcasses.

III. Renewable Resources

Natural resources like grasslands, forests, wildlife and fisheries, are considered renewable because they can provide a crop of food or materials year after year. The grassland-bison community was an enormously productive renewable resource.

However, resources are only renewable if they are managed properly by maintaining habitats and controlling harvesting. If a kind of plant or animal becomes extinct, its productivity is lost from Earth forever.

Passenger pigeon (left) and Carolina parrakeet (right)

Most organisms can be harvested to some extent by predators and maintain a healthy, stable population. However, over-harvesting of plants and animals by humans has been a major cause of extinction in the past. The pictures on this page show two birds that were hunted to extinction for meat and feathers in the 1800’s. These species were lost because some people valued immediate jobs and income more than the potential for future harvests. The responses of concerned citizens and law makers came too late for those animals. Luckily, people came forward in the nick of time to save the bison.

The return of the bison as both a free-roaming and ranch-raised species has been made possible by thousands of private citizens including: Native Americans, journalists, artists, land owners, law makers, and scientists.

IV. Who Helped Save the Buffalo?

The buffalo nickle and ten-dollar bill helped promote conservation efforts.

From The American Buffalo in Transition, J. Albert Rorabacher

More than 100 years ago many people were concerned about saving some of the great bison herds. Many Western settlers were keenly aware of the sharp decline in the populations. Various laws were passed to protect the endangered species.

- In 1864, the Territory of Idaho outlawed the slaughter of buffalo, but enforcement was controlled by the military, which allowed the mass killing to continue.

- In 1871, Wyoming passed a similar law. Colorado outlawed the practice of leaving meat on the plains to decay.

- In 1874, Congress passed a bill “to prevent the useless slaughter of the Buffaloes within the Territories of the United States.”

In The Buffalo Book, author David Dary describes the efforts of a number of men who hung up their rifles to preserve the buffalo. Although some had profit in mind with the idea of domesticating the buffalo, most were genuinely concerned about saving the animal from certain extinction. Samuel Walking Coyote, a Pend d’Oreille Indian, saved 6 orphaned buffalo calves in 1872, and returned with them to the Flathead Reservation in Idaho. He eventually sold his small herd of 13 animals to Michael Pablo and Charles Allard in 1884. This small herd would become vitally important in bringing the buffalo back from the edge of extinction.

William Hornaday, a taxidermist for the Smithsonian Museum, was one of the most influential persons to help save the bison from extinction. When he traveled to Wyoming in 1887 to collect bison specimens for a museum exhibit, he was shocked to realize that only a few hundred animals remained scattered across the west. Hornaday helped establish a breeding herd at the New York Zoological Society, which eventually provided bison offspring for parks and reserves around the country. In 1905, he established the American Bison Society, which pushed Congress to create the National Wichita Forest Reserve in southwestern Oklahoma and the National Bison Range on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana. The American Bison Society was also successful in pressuring Congress to fund protection for the few remaining bison in Yellowstone Park.

The rapid extermination of the seemingly endless herds shocked many Americans who had grown to love and respect the wonderful shaggy beast. The bison became a symbol and a rallying point for citizen action; it was featured on stamps, paper money, and coins to promote national conservation efforts. From our vantage point today, we can look back over the story of the bison and learn lessons from the tragic series of events that brought so many Native American cultures, animals, and plants to the brink of extinction. Learning about the values of biodiversity can help us avoid the mistakes of the past.

LB2.2. Investigation:

Graph the Population of the Buffalo

Historians and biologists have tried to estimate the pre-1500’s bison population from descriptions and estimates of the early hunters and travelers. These and the estimates of buffalo numbers during the 1800’s are “informed guesses,” since scientific sampling methods were not used by early observers. Nevertheless, the crude estimates do indicate a dramatic trend. Using the data below, graph the population of bison from pre-European settlement to the present. Label key points on the graph to show significant historical events from this chapter that help to explain changes in the buffalo population.

Population Estimates for North American Bison

| Researcher | Date | Estimate |

|---|---|---|

| T. McHugh | 1500s | 30,000,000 |

| E.T. Seton | 1850 | 20,000,000 |

| C.J. Jones | 1870 | 14,000,000 |

| William T. Hornaday | 1889 | 1,091 |

| E.T. Seton | 1895 | 800 |

| Mark Sullivan | 1900 | 1,024 |

| Dr. Frank Baker | 1905 | 1,697 |

| American Bison Society | 1910 | 2,108 |

| American Bison Society | 1914 | 3,788 |

| American Bison Society | 1920 | 8,473 |

| American Bison Society | 1929 | 18,494 |

| Henry H. Collins | 1951 | 23,154 |

| J.A. Rorabacher | 1970 | 30,000 |

| J. R. Luoma | 1993 | 120,000 |

| National Bison Assoc. | 2000 | 364,000 |

Question 2.4

How have these species been affected by changes to the Great Plains?

LB2.3. Investigation: Biodiversity Issues

There are many conflicting viewpoints about how public lands and resources should be managed. As with every controversy, there are differing opinions among land owners, government agencies entrusted with protecting the public’s interest, and conservation groups that represent a wide spectrum of citizens. The following issues are currently being debated in the Great Plains states:

Creating A Buffalo Commons

Across the arid plains, ghost towns have appeared as poor ranchers and farmers leave their boarded-up storefronts and empty farmhouses behind. One innovative proposal for bolstering the failing economies of plains communities is to turn thousands of square miles of damaged and marginal land into a vast nature preserve called the Buffalo Commons. Tourists could experience an American Safari where grazing animals like the bison and pronghorn, and predators like wolves could roam freely.

Create a Private Land Cooperative

Another proposal for eastern Montana is called “The Big Open.” To stimulate jobs and revenue from tourism, ranchers in the region would collaborate in restoring native populations of game animals. Tourists and sport hunters would pay fees to use the wild areas for recreation. Hunters would also pay the landowners fees to hunt on private lands. The proposed natural area would support 75,000 buffalo, 150,000 deer, 40,000 elk and 40,000 pronghorn.

Reintroduce Wolves to

Western Parks and other Public Lands

Scientists and conservationists have taken steps to restore wolves to Yellowstone, The Grand Tetons, and New Mexico. They point out that populations of bison, elk, and deer have increased with protection and are adversely affecting the health of the native vegetation. Restoring wolves to the parks would have the added benefit of improving the genetic health of the herds by allowing a natural predator to eat the weak animals. Some land owners oppose the reintroduction of the predators because they believe the wolves will also attack their livestock.

Choose a biodiversity issue of interest to you and your community. Research both sides of the issue. Write a letter to the editor of your newspaper recommending a course of action.

V. What Did We Learn from the Bison?

There are many reasons for the accelerating rate of extinction throughout the world. The story of the bison illustrates some of the major causes of loss of biodiversity worldwide.

Introduction of non-native species. The replacement of the hardy bison with domestic cattle has contributed to a loss of native species because there is less habitat available. Cattle are more vulnerable to predators, even small ones like coyotes. Eventually, wolves and grizzly bears were exterminated from the region to protect cattle, and vast areas of rangeland were treated with poisoned bait to control coyotes.

The introduction of non-native species can set off a chain of events that causes a decline in native plants and animals throughout a region. Cattle and horses from Europe have changed and degraded the Great Plains grasslands. The cattle carried diseases such as brucellosis. Brucellosis affects the reproductive system of mammals, and now is found in native populations of elk and bison. Many species of European plants traveled to North America clinging to the hair and hooves of the livestock. Today many have become “pest plants” throughout the West.

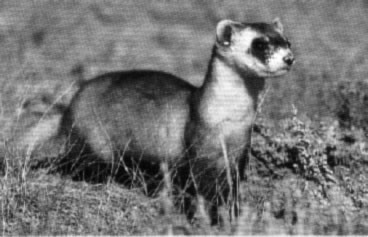

“Pest” Control. Overgrazing by cattle, as well as predator control benefited the prairie dogs, whose “towns” sometimes extended over hundreds of acres. The prairie dogs competed with the cattle for grass. Ranchers attempted to reduce prairie dog populations through the widespread use of poisons. The poisons also killed predators such as black-footed ferrets, badgers, owls and eagles. The practice of poisoning coyotes and prairie dogs continues to receive government funding to this day. In Chapter 7 we will investigate how the Endangered Species Act of 1973 has been pivotal in saving predators such as the black-footed ferret and the peregrine falcon from extinction due to poisons in the food web.

New Technology. Technology can bring about the extinction of a species. The long-range Sharps rifle and the railroad certainly contributed to the rapid decline of the buffalo. Barbed wire fences have been a major cause of mortality for pronghorn antelope. As we will see in Chapter 7, sonar technology and plastic nets are major causes for declining fish populations worldwide. What are some other technological advances that have led to the decline of species?

Military Operations. Throughout human history, military operations have led to the destruction of wildlife and other natural resources, as well as genocide. Historical records reveal that U.S. military personnel obstructed conservation of the buffalo during the critical period of 1874-1889 in order to control the Native Americans who depended upon the bison. In more recent times, World War II, the Korean War, herbicide defoliation of forests in Vietnam, the burning of oil fields in Kuwait, and the mass killing of people in Africa are examples of how modern military weaponry have affected the biodiversity of the planet and revealed the vulnerability of human ethics in times of war.

VI. In Conclusion

As we have seen with the bison, commercial exploitation and changes in habitat to provide farms and settlements for the invading culture can quickly eliminate plant and animal species as well as less powerful human cultures.

Fortunately, the bison were not exterminated. They were brought back from the edge of extinction by people with compassion and foresight. It is also fortunate that despite the widespread decimation of Native American populations, many have survived and are working to preserve their rich cultures.

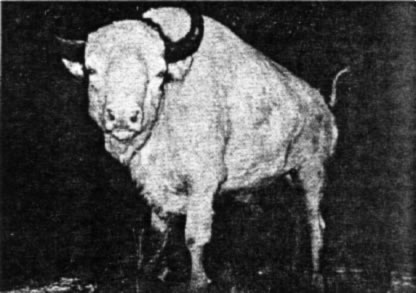

Big Medicine. Born on the National Bison Reserve in 1933, this rare white bull bison was a favorite tourist attraction until his death in 1954. White buffalo were occasionally observed in the great herds that roamed the plains in the earl 1800s, but these animals were quickly shot for their valuable hides.

2.5. Propose environmental conditions that might favor the increase of this color of variant in bison populations.

We should not end the story of the bison by leaving a wrong impression—that only a few members of each species need to be saved in order to preserve the biodiversity of our planet. When populations are greatly reduced, important inherited characteristics may be lost. In the next chapter, we will investigate why conserving diversity within populations is important for enabling species to adapt to new environments and new circumstances, such as climate change, new diseases, and competitors. Scientists are continuing to explore ways to conserve bison genetic variability within the constraints of the limited habitat in national parks and reserves.

Bison Web Sites

National Bison Association – http://www.bisoncentral.com

Great Plains Buffalo Association

Texas Bison Association – https://texasbison.org/

National Wildlife Federation – http://www.nwf.org –search for buffalo.

Intertribal Bison Cooperative – http://www.intertribalbison.org