AN2. A History of Forest Use in the Pacific Northwest

Chapter 2

Just as you are creating changes in your “ecosystem in a bottle,” humans are changing the ecosystems of the world’s forests. This chapter summarizes the history of those changes.

In the year 1800, approximately 1 billion people lived on our planet. Now we number nearly 6 billion, and our population continues to grow at the rate of 250,000 people a day.

The impact of the growing human population on the forests of the world has been immense. Forests have been cleared to grow food and to graze cattle. They have been cut to make room for cities and superhighways. Trees have been logged to produce lumber for building, fuel for heating and cooking, and raw materials for paper and dozens of other wood products. Between the years 1960 and 1990, approximately one fifth of all tropical rain forests were burned or cut down, and a great many of the species that once lived in those forests have become extinct.

Fortunately, the loss of forested land has been largely halted in the United States and most other developed countries. We have already cleared all of the forests on soil suitable for agriculture. The remaining forests are in mountainous areas, or on soils that are more productive for growing trees than crops. Nonetheless, we are still engaged in a very active controversy over the use of forests. The controversy is about whether or not logging companies should be permitted to cut old growth forests—forests that have never been logged before. Many of these forests contain large trees that are hundreds, and in some cases, thousands of years old, as well as plant and animal species that may not survive in forests with smaller, younger trees.

The question of whether or not to cut old growth forests illustrates how we are impacting natural systems. As citizens, we have control over how our forests are used.

Do you have an opinion about the use of old growth forests? How do you react to the following news story?

I. The Great Road Building Controversy

On January 10, 1998, the White House announced its intention to call a halt to construction of new roads in most National Forests. To understand why this was such a controversial issue, it is important to understand the difference between National Parks and National Forests.

(Photo by Cary Sneider)

National Parks are protected areas, where logging is not permitted. National Forests are large, publicly owned tracts of forested land that are generally made available to logging companies.

The president’s decision to halt the construction of new roads would protect large areas of old growth forests. The new rules would not cover forests that are under 5,000 acres in size. (An acre is a little smaller than a football field.) Also, they would not cover forests in the Pacific Northwest or Alaska.

Write down your ideas in response to the following questions, before continuing with this chapter.

Q 2.1. Most of the objections to the president’s decision have come from the wood products industry. What do you think are the strongest arguments on the side of the wood products industry to continue to permit new roads in National Forests?

Q 2.2. Most environmentalists were pleased with the plan, although many would like to see the plan include the large forests in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, as well as areas as small as 1,000 acres. What do you think are the strongest arguments on the side of the environmentalists to halt all road building in National Forests?

Q 2.3. What is your personal opinion of the new rules, and why?

Q 2.4. When George Bush won the Presidential election there was discussion in the news about reversing decisions of the Clinton administration. Search the internet to find out where this issue stands today.

II. What Happened to the Forests?

(Photo by Freeman, courtesy of the BioScience Library, University of California at Berkeley)

To a large extent the issue of whether or not to cut old growth forests is a story of the Pacific Northwest, because most of our nations’ remaining old growth forests exist there.

Before the coming of human settlers, the world’s largest temperate rain forest carpeted the northwestern United States and adjoining portions of Canada. A variety of coniferous (cone-bearing) trees covered 90% of the land area of Washington and Oregon, and substantial parts of California. The most common trees in this region were fir, spruce, cedar, hemlock, and pine. Further to the south, in California, were stands of giant redwood trees, including some that first took root 3,000 years ago.

Native Americans The first human settlers probably came to this region about 10,000 years ago, from Asia, traveling over the land bridge that once existed between Siberia and Alaska. Although small bands of settlers may have come long before, the only conclusive evidence of large scale settlements—including a great many arrowheads and other artifacts—dates from this period of time.

Early European settlers to the region reported that Native Americans purposely set forest fires to clear land for human use. Scientists who have studied pollen buried in layers of earth sediment found evidence that Native Americans may have been conducting controlled burns for thousands of years.

For the most part, the fires set by Native Americans were not wild infernos that we normally associate with forest fires. They were set annually, so that brush and dead wood did not have time to build up. And, they were set at times of the year when rain and moisture would keep the intensity of the fires low. The effect of the low intensity burns was to preserve the large trees, while clearing brush and dead wood. When forests recovered after fires, they increased the production of acorns, which the Indians used for food.

The Native American concept of personal property was also different from the modern view that an individual can buy, own, and sell land. While tribal and family groups had access to certain forested areas for their daily use, they did not consider themselves to be the owners, but rather caretakers, or stewards of the land. Consequently, cutting down all of the trees, or taking all of the salmon or deer on a parcel of land could not be justified by claiming that any individual owned it, and could do with it whatever they chose.

British and American fur traders who came west starting in the late 1700s did not find a “virgin wilderness.” Native Americans had lived in the forest for thousands of years, hunting, fishing, cutting trees, and setting forest fires. But the overall impact on the forest during this period was far less than in later periods. Total forest cover remained about the same (90%), forest growth more than recovered after burns, and the abundance and variety of plant and animal species was probably about the same as before people came to North America.

Fur Traders

The first widely publicized journey to the Americas by a European explorer was made by Christopher Columbus in 1492. Within a few decades the heavily forested region of the Pacific Northwest was visited by Spanish, Russian, and British ships. However, it wasn’t until 1778, when English Captain James Cook and his crew spent a month in the Pacific Northwest, that exploitation of the region’s resources began. In addition to cutting trees to replace masts for their ships, Cook’s crew traded with the Indians, exchanging European goods for sea otter fur pelts. They then traded the pelts in China for fantastic profits, before returning to England. The publication of Cook’s journals started the fur trade, and from that time on Great Britain and the newly created United States began to battle for control of the region.

The American Robert Gray explored the Pacific Northwest by ship in 1792, and just over a decade later, Merriwether Lewis and William Clark crossed the American continent by land. In the following decades, many American and British traders came by land and sea to make their fortune from the otter, mink, beaver, and other fur-bearing animals. To these traders, the dense forests seemed an impenetrable barrier.

For the first few decades of the 19th century, Native Americans played a very important role in the fur trade. With their understanding of how to hunt, they did business with both American and British traders. However, contact with Europeans meant contact with European diseases, especially smallpox. Disease, warfare, and conquest by ever larger numbers of Europeans, led to catastrophic declines in the Native American population throughout the continent, including the Pacific Northwest.

The first effort to cut down some of the large, ancient trees to clear land for the use of the fur traders was described by Alexander Ross.

After placing our guns in some secure place at hand, and viewing the height and breadth of the tree to be cut down, the party, with some labor, would erect a scaffold round it; this done, four men—for that was the number appointed to each of those huge trees—would then mount the scaffold, and commence cutting, at the height of eight or ten feet from the ground… Indeed, it sometimes required two days, or more, to fell one tree. So thick was the forest, and so close the trees together, that in its fall it would often rest its ponderous top on some other friendly tree… giving us double labor to extricate the one from the other, and when we had so far succeeded, the removal of the monster stump was the work of days.”

—Alexander Ross, Adventures of the First Settlers on the Oregon or Columbia River, 1810-1813

The fur trade period lasted just four decades. By the 1840s, the Native American population was tragically decimated, and few fur-bearing animals were left to hunt. The fur trade might have continued for a while longer, but consumer preferences changed. Silk hats were “in,” and beaver hats were “out.” Nonetheless, at the end of this period the vast forests of the Pacific Northwest were still largely intact.

Settlers

The early settlement period began as the fur trade ended, in the 1840s. Thousands of Americans traveled west, lured by the descriptions of explorers and fur trappers of the vast wilderness waiting to be “tamed.”

Stories of this period, until the last decade or two, emphasized the pioneering spirit of the first settlers, their triumphs over natural disasters, and their battles against hostile Indians. Recently, books and movies have told the story from the Native American point of view, emphasizing the toll taken by the early settlers on Native American populations and on the environment. The actual story is a far more complex interaction of people from many different cultures, with different ideals and visions of how the world should be.

Still, the early settlers did not transform the forests on the scale that we see today. The early settlers preferred to plant crops and graze cattle on open grasslands, rather than cutting the large trees. While the need for lumber grew steadily, cutting the huge trees and sawing them into boards to build houses had to be done by hand, and the going was very, very slow.

19th Century Loggers

(Photo by Ericson, courtesy of the BioScience Library, University of California, Berkeley)

The logging industry picked up steam in 1848, when gold was discovered in California. With vast numbers of people coming to California over land and by ship, towns sprang up seemingly overnight. The port city of San Francisco grew rapidly, at the expense of the forests for miles around. Large portions of the city burned to the ground more than once, further increasing the need for lumber to rebuild homes, hotels, and businesses.

The first sawmills were pits dug into the ground. The end of a large log was pushed over the pit. One person stood on top of the log, and another person stood in the pit, under the log. Using a long saw, the two men slowly sawed the log into long flat planks of lumber.

Soon, steam engines were used to power the saws. In 1852, two men purchased an old steamboat in San Francisco and loaded it with machinery for a wood mill. They traveled north along the coast until they reached a bay where the city of Eureka now stands and ran the ship aground. They built the sawmill alongside the ship, using its engines to drive the saw. The mill employed about 40 men who lived in the ship itself. By 1854, nine millswere operating in the area.

As San Francisco and other cities along the coast continued to grow, more and more people went into the lumbering business. Still, the work of felling the large trees was slow. It was not uncommon for two men to spend as much as a week of steady work to bring down a single giant tree. Frequently, the trees shattered, wasting a lot of the wood.

Transporting the large logs to the mills was usually done by teams of oxen. The strong oxen would drag the logs over “skidroads,” made of smaller logs, to the mills. But within a few years railroads were built to bring the logs from the forests to the sawmills. Some logs were loaded directly onto ships. Between 1860 and 1864, three hundred small ships operated up and down the California coast, bringing logs from the forest to the sawmills.

Photo by Ericson, courtesy of the BioScience Library, University of California, Berkeley.

20th Century Loggers

During the 20th century, the technology of cutting and transporting trees improved dramatically. Cutting trees on hillsides and sloped terrain is now done by loggers with large chain saws. On flat terrain, a machine called a feller-buncher is used. This machine can cut an entire tree at ground level, lift it, and place it in a stack. It can cut its way through the forest, making its own road as it goes.

Logging companies use a variety of methods, depending on their current and future plans for a given forest. Clearcutting involves complete removal of all trees. Selection cutting refers to the removal of individual trees, or small groups of trees; and salvage means only removing trees that are diseased or have already fallen.

Modern logging techniques include two processes that were unknown in the last century. One of these is to reduce waste by using every scrap of the wood. Small pieces of wood, chips, and even sawdust are now processed in large machines that press the wood under high pressure into sheets (such as particleboard) that can be used in construction. The other process is replanting.

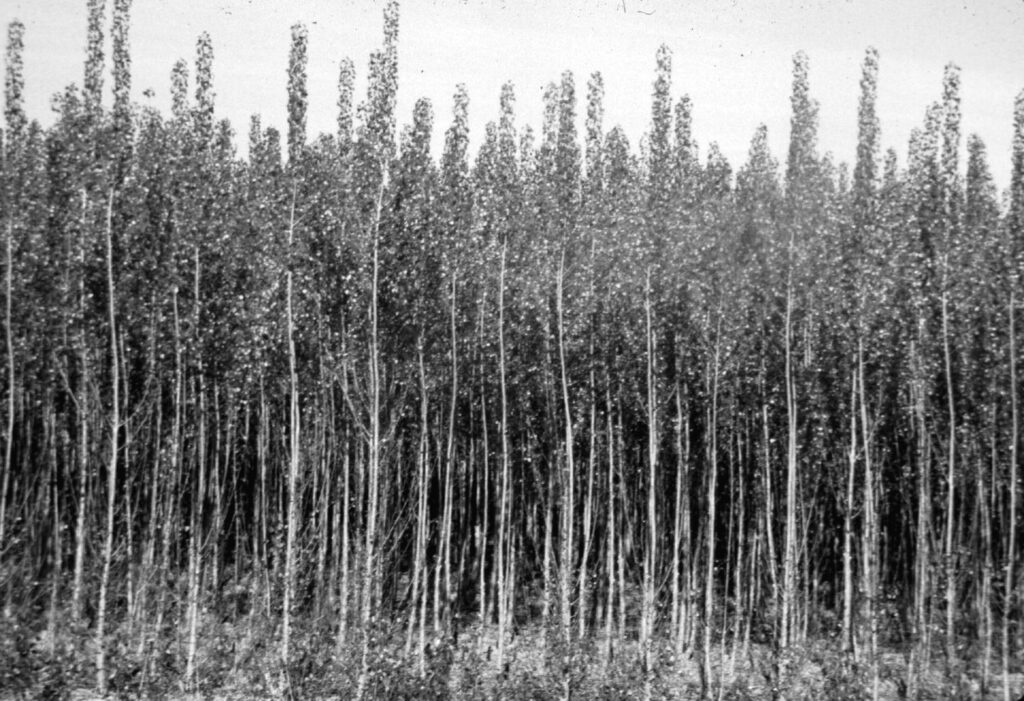

(Photo courtesy of Pacific Lumber Company).

Most logging operations in the Pacific Northwest today take place in managed forests. Managed forests have been logged at least once before. Once harvested, they are replanted with native varieties, such as Douglas fir, that are resistant to disease, grow quickly, and produce good lumber. The trees in managed forests are all the same age, and are harvested whenever the trees mature—every 30-100 years—depending on the types of trees and growing conditions.

Tree plantations are also harvested and replanted, but they are a special kind of managed forest. They are planted with trees such as poplars or alders that grow very quickly, and are ready to harvest again in as little as seven years. Trees that grow so quickly are not very dense (unlike hardwoods, such as maple or oak), so they are more suitable for making into paper than into lumber. In plantations, trees are planted in rows, so they appear quite different from managed forests, which are replanted randomly. Both plantations and managed forests are different in appearance from old growth forests.

Old growth forests (sometimes called “ancient” forests) have not been logged for at least 200 years. They contain a variety of different tree species of varying ages, including some very large trees that are hundreds, or even thousands of years old. Today, an estimated 95% of the forested land in the Pacific Northwest has been logged. What to do with the remaining 5% is a hotly debated issue.

Lumber companies prefer old growth trees for a number of reasons. The very large trees provide wide boards free of knots that are especially suitable for moldings and furniture. A single tree can provide as much as $200,000 worth of lumber. Lumber companies point out that mature trees will eventually die, rot, and fall, destroying other trees in the process. In their view, it is better to harvest the trees and plant new ones in their places. Instead of allowing the trees to rot, harvesting them provides jobs and a much-needed building material for people to use.

People who prefer to preserve old growth forests in their native state—generally called environmentalists—point out that allowing trees to complete their life cycles is important to preserving the abundance and diversity of plant and animal life in the forests. The large trees provide a variety of habitats for plants and animals not found in managed forests or tree plantations, and the old fallen trees provide homes for small animals, and return nutrients to the soil that are lost when the trees are harvested.

Both lumber companies and environmentalists cite the results of scientific studies to support their opinions about what to do concerning old growth forests; but the decisions are made by citizens. In some cases, this is done by voting directly on what to do with old growth forests; and in other cases by voting for or against politicians whose records show where they stand on environmental issues. In order to make intelligent decisions, citizens need to understand the arguments—including the scientific arguments—on both sides of each issue.

AN2. Investigation: Tree Impact Study

Your goal in this study is to document the impact of a large tree on the environment of your school or community. The project will be more fun and productive if you have one or two partners to work with.