AN3. Case Study: The Headwaters Controversy

Chapter 3

The historical summary in the previous chapter may seem remote and not our doing. It happened a long time ago, and there isn’t anything we can do about it. But as you’ll see in this chapter, people continue to make decisions about whether or not to change forest ecosystems.

More than 1,000 people gathered in Arcata Plaza Sunday to rail against any new logging in ancient groves left unprotected by a moratorium. “We’re going to keep fighting just as we have for the last 10 years,” said Cecelia Lanman, director of Garberville’s Environmental Protection Information Center. “They’ve underestimated us again. This is the start of the next 10 years of the fight to save every last ancient stand.” Students and professors from Humboldt State University mingled with Earth First protesters and other logging foes, gathering aid for tree-sits and blockades. One protester carried a sign, “It Takes A Pillage to Raze A Forest.” A father boasted that his 16-year-old daughter skipped school to sit in a tree to try and stop logging. Sitting with his friends, Byron Pontoni, a third-generation member of a Humboldt County family, said his friends who are foresters want to start cleaning out the forests. “I think they should be able to take what’s on the ground and leave what’s standing. I’m not an extremist one way or another.”

— San Francisco Examiner, September 30, 1996

What could bring thousands of protesters to a rural area in Northern California, where lumbering has been a way of life for more than a hundred years? In brief, it is a particular area of privately owned old-growth redwood trees that are now scheduled to be logged. Towering more than 300 feet high, and 18 feet or more at the base, some of these giant trees have been growing since the birth of Christ. The rich ecosystem of the Headwaters Forest is home to the Northern spotted owl, bald eagle, Coho salmon, and other endangered species. Although the contested grove covers just 3,000 acres, the Pacific Lumber Company—which owns the forest—claims the giant trees are worth $700 million.

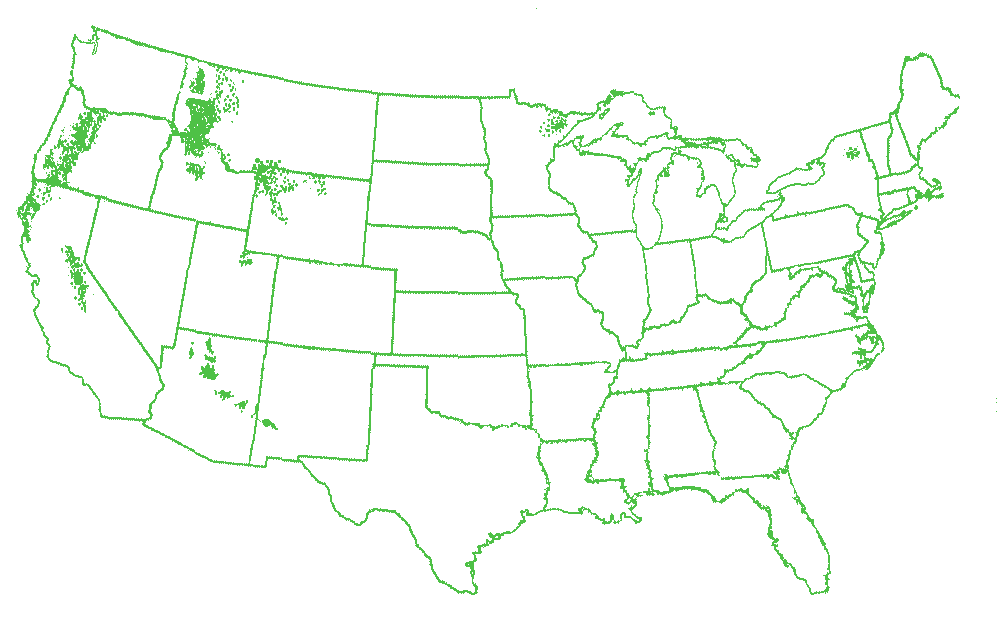

While the overall forested regions in the United States are no longer shrinking, old growth forests have dwindled to just a few percent of what they used to be. The controversy is whether or not these remaining old growth forests should be logged or not. There are valid arguments on both sides. In this chapter, you’ll hear about the controversy from the point of view of the wood products industry, environmentalists, and a U.S. Senator.

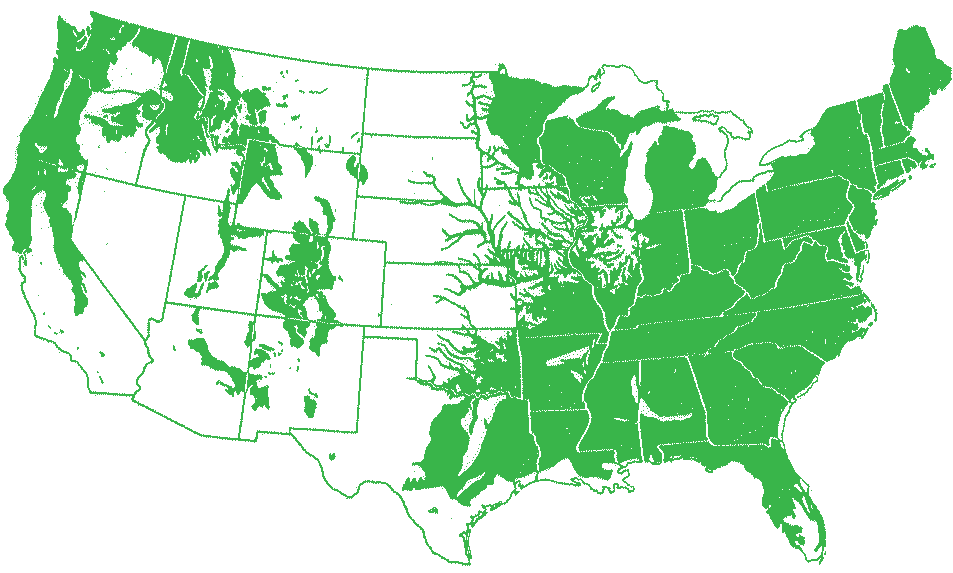

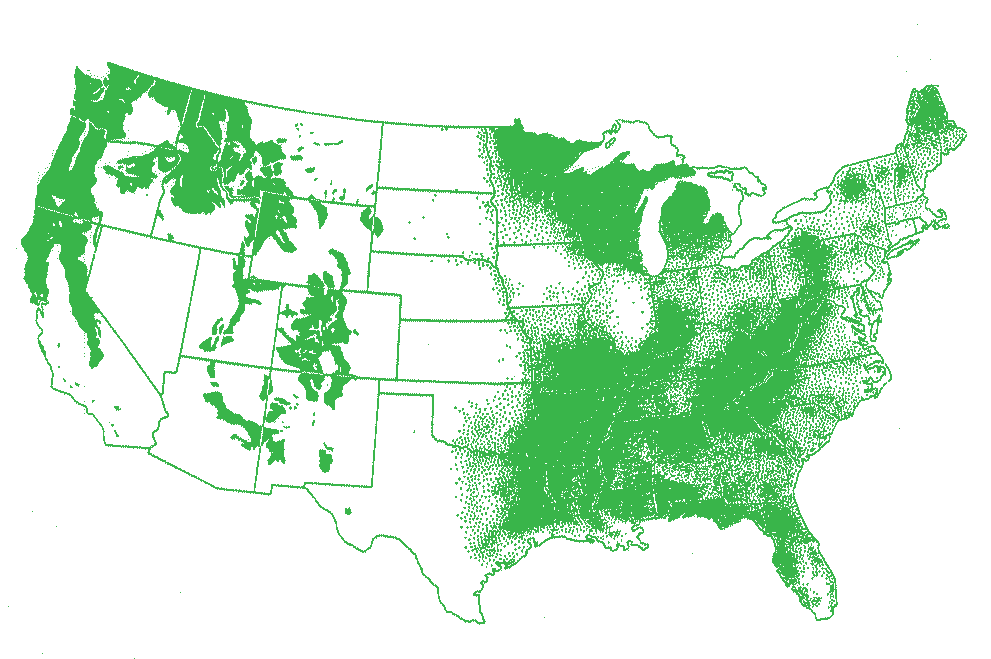

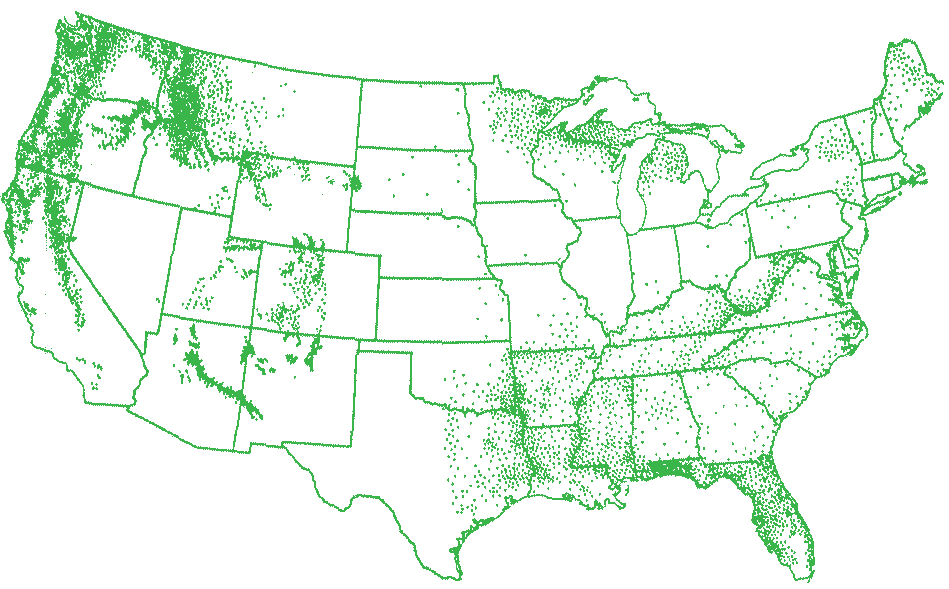

Remaining Old Growth Forests

The shaded areas in the illustrations below show the remaining old growth forests in the United States in 1620, 1850, 1926, and 1990. The images are composed of dots each of which represents an area of 25,000 acres of old growth forest. (Data are from Paullin, Charles Oscar, Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Edited by John K. Wright, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 1932, 1975; Findley, Rowe, and Blair, James P. “Will We Save Our Own?” National Geographic, vol. 178, no. 3, September,1990, page 120; and The Wilderness Society.)

AN3.1. Investigation: How much old growth forest was lost?

Make estimates of how much old growth forest we actually lost in the past few hundred years. How much was lost in your state?

If you have a computer, you can use AnalyzingDigitalImages software to make measurements with the 4 maps, because they are contained in the software. After launching the software, look for the “Old Growth Forest Time Series.”

Questions:

3.1 How much old growth forest was lost in your state?

3.2 How does your state compare with other states in terms of amount of old growth forest lost?

3.2 How does your state compare with the national average and to other states in terms of amount of old growth forest lost? Since you are restricted to rectangular boxes which can’t match most state boundaries, your measurements are necessarily approximations.

3.3 Which state lost the least old growth forest?

3.4 How much old growth forest was lost in your region, in a particular size box around your city or town?

3.5 Compare the loss of old growth forest in a particular size box around your city or town with that of identically sized boxes around cities or towns where you have friends, relatives, or a city/town that interests you.

3.6 Are there any areas that had an increase in old growth forest during a particular time? If so, how could this happen?

3.7 Prepare a written statement summarizing your findings and be ready to present it to your classmates.

3.8 What additional questions come to your mind that you cannot answer with the data given? Write these along with your summary statement.

Update April 2023: See article How much U.S. forest is old growth? It depends who you ask [https://www.science.org/content/article/how-much-u-s-forest-old-growth-it-depends-who-you-ask] by Gabriel Popkin, Science Magazine. Excerpt: Last spring, President Joe Biden surprised forest scientists when he ordered the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to inventory their holdings of mature and old-growth forests by Earth Day 2023. The order triggered a scramble for the United States to, for the first time, formally define what constitutes “mature” and “old-growth” forests and to apply those definitions across millions of hectares of land. Now, the agencies have delivered their findings: Of the nearly 72 million hectares of forest managed by the two agencies, 45% are mature and 18% are old growth, according to a report released last week. The figures far exceed previous estimates published by nonfederal researchers and are likely to add fuel to an already raging debate about how to manage older forests and make them resilient to climate change.

…But Greg Aplet, a senior forest scientist with the Wilderness Society, says “the methods [the agencies] used are not transparent.” In January, Aplet co-authored a paper finding that only 37% of USFS and BLM forests are mature or old growth. The new federal report classified as mature many forests that most researchers would consider young, Aplet says, a result that “strains credulity.” Over the past year, USFS and BLM officials asked tribal groups, scientists, and others to weigh in on how best to define old-growth and mature forests. The agencies then assembled a research team tasked with capturing the complexity of the nation’s forests in a few defensible numbers; some team members worked nights and weekends and skipped vacations to meet the April deadline. One of the team’s top challenges was coming up with universal definitions that could span the vast diversity of forested ecosystems, from lush rainforests of the Pacific Northwest to dry forests of the Southwest, where even old trees remain small and grow sparsely. “They were given a nearly impossible task,” Eisenberg says.

…Several other research groups have recently published their own methods for defining old-growth and mature forests. Aplet and his colleagues used equations to estimate how much carbon is contained in a forest based on its age, type, and site quality. They defined old-growth forests as those that had reached 95% of their potential total carbon accumulation and mature ones as those that had reached the age of peak average carbon accumulation. A different study published in September 2022, which used satellite data to estimate canopy height, canopy cover, and above-ground living biomass, found that mature and old-growth forests combined occupied 23 million hectares, or 30%, of USFS and BLM forestland….

[end of article excerpt]

VIEWPOINT: The Environmentalists

The following is from Communication Works of August 1997 and other Headwaters materials.

Use is courtesy of the Headwaters Sanctuary Project.

“The ancient groves of Headwaters Forest display the most outstanding characteristics of the delicate redwood ecosystem. Today so little of the old-growth redwood forest remains that every bit is precious, both for wildlife living there and the future viability of the ecosystem as a whole.

Why the Fuss Over A Few Big Trees?

“In little more than a century, the two-million-acre ancient redwood forest system has been cut down to a few scattered islands. Headwaters Forest contains the largest unprotected ancient redwood forest left in the world. It is a remnant of a once-abundant high-elevation ancient redwood forest. As such, it is a critical area for species which need that forest type for survival. The marbled murrelet, a seabird that nests on the large limbs of ancient trees, depends entirely on Headwaters and only two other places in California. The coho salmon, whose numbers have drastically declined the last few decades, need the cold clean water that filters from this ancient forest. It is estimated that five to ten percent of the remaining wild coho salmon in California spawn in drainages that flow from Headwaters Forest.

“Redwood is one of the fastest-growing tree species, but a forest is much more than trees. Redwood forests develop the greatest volume of living matter per acre on Earth, as much as ten times that of tropical rain forests. Redwoods grow two to three feet per year under ideal conditions, reaching a canopy height as high as 367 feet in 200 years.

“As they age, redwoods’ thick bark and lack of resin make them almost entirely fire- and insect-resistant. Venerable elders among us, redwoods can exceed 2,000 years of age.

“Redwood trees have shallow root systems that penetrate only about six feet into the thick forest floor while spreading out 60–80 feet and intertwining to anchor themselves against heavy winds. For this reason, redwoods are extremely vulnerable when isolated in roadside stands or fragmented by logging.

“Ancient forests have evolved over millions of years to reach a climax state with individual trees more than a thousand, even two thousand, years old. A multi-layered canopy, a mix of tree species and ages, large standing dead trees (snags), and fallen trees comprise the basic structure of the ancient forest. The complex interplay of plants and animals—the ecosystem— depends on these diverse elements. Industrial forestry destroys this biological diversity by reducing the landscape to an impoverished simple state, single-species, single-age tree farms.

“Current industrial practices in the redwood region promote an average rotation age (cutting cycle) of 40 years or less. Redwood doesn’t even begin to acquire its desired rot-resistant properties until it is approximately 80 years old. And powerful carcinogenic pesticides, routinely used in clear cut areas to kill brush and hardwoods, leach in the water table, polluting the groundwater and killing fish.

“Conservation biology shows that preserving forest islands surrounded by trees farms is a hollow gesture. Such isolated “tree museums” lack biological integrity and cannot effectively protect ancient forest habitat. To protect the wild area, we must draw together the fragments of old growth by purchasing and restoring the adjacent cut-over forests. Buffers around the ancient groves will help ensure that the interior forest habitat necessary for dependent species survival is not lost to edge effect—changes in microclimate due to exposure to more dramatic weather patterns and invasive species. Connecting landscapes between groves will allow species to interbreed to avoid local extinctions.”

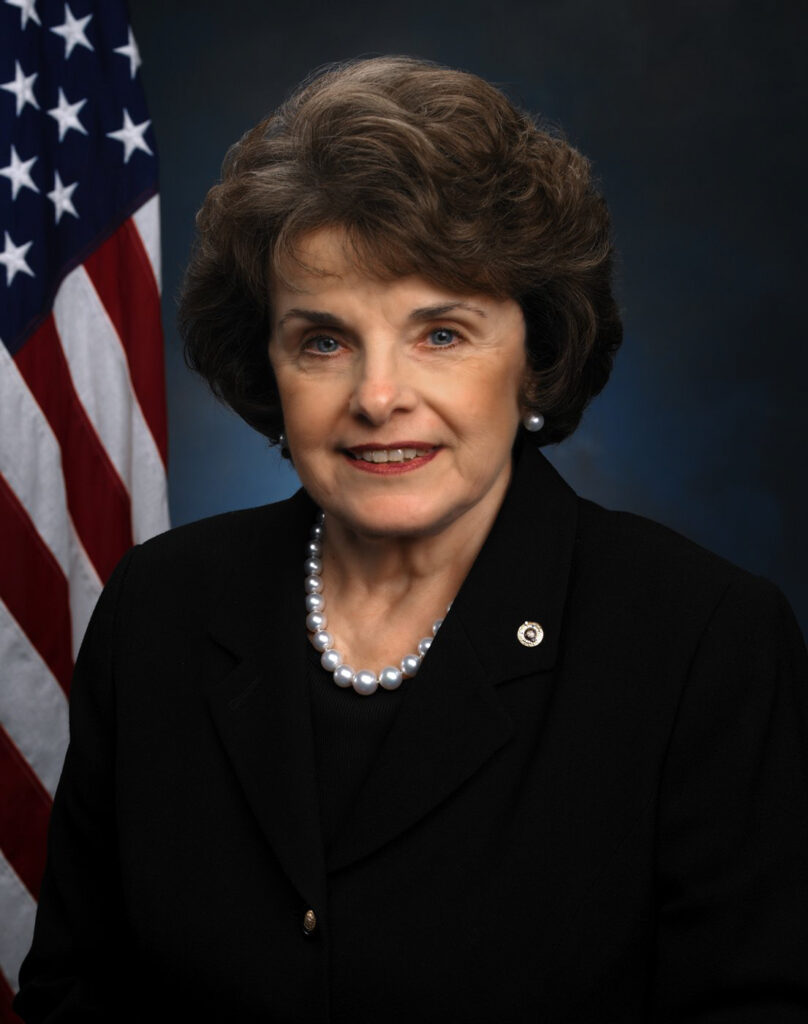

VIEWPOINT: The Senator from California

The following is from an article by Sen. Dianne Feinstein, which was published in the San Francisco Chronicle on October 7, 1996—©San Francisco Chronicle. Reprinted with permission.

The Last Best Hope for Headwaters

Ten years seems like an eternity to those of us who have participated in what seemed like an endless debate over preserving the Headwaters Forest. Yet it is merely a fraction of time in the 2,000 year life of the magnificent redwoods over which this increasingly pitched battle has been waged.

In the decade-long standoff, no solution has ever been within our grasp. Two statewide bond initiatives on the ballot that would have raised funds to purchase Headwaters were rejected by California voters. [In 1990, California voters turned down a ballot initiative to buy the Headwaters Forest. It was a close vote: 47% in favor; 53% against.] Federal legislation to acquire the Headwaters failed as well. The State of California says it has no legal recourse to prevent Pacific Lumber from logging its own property. And, after staying out of the Headwaters for 10 years, Pacific Lumber made it clear that the company intended to begin salvage logging immediately after the marbled murrelet nesting season ended two weeks ago. Prospects for a resolution certainly seemed dim as the logging date approached.

Against this backdrop I was asked a month ago to help move the negotiations forward. After more than 100 hours of intense negotiations, a tentative agreement was hammered out for the federal and state governments to jointly purchase the most sensitive areas of old-growth redwoods—the Headwaters Forest and Elkhead Springs Grove—and enough surrounding acreage to protect these fragile ecosystems, nearly 7,500 acres. The price is $380 million in cash and/or assets.

Is it everything the environmentalists wanted? No—they wanted 60,000 acres. This was not an obtainable goal; we couldn’t afford to purchase that much land. Is it everything Charles Hurwitz and Pacific Lumber wanted? No—they wanted substantially more money. They believe the Headwaters alone is worth in excess of $700 million. We couldn’t afford that. It is a compromise, and the agreement is as fragile as the ecosystem we are trying to protect.

But it is important to understand that the agreement is a historic move forward. Not only does the agreement—if it is completed—protect the heart of the ancient redwood groves, but it is also the largest effort at habitat conservation in U.S. History.

Under the tentative agreement, which was signed by the U.S. Department of the Interior, the State of California, Pacific Lumber and its parent company, Maxxam Inc., the federal and state governments will purchase 7,500 acres of forest. The preserve will include about 3,000 acres of old-growth redwoods known as the Headwaters Forest, 425 acres of old-growth known as Elkhead Springs Grove, plus an additional 4,000 acres of second-growth land to provide an environmental “buffer zone” around the most sensitive areas.

In addition, Pacific Lumber will submit a plan for habitat conservation (known as an HCP) to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in order to conduct logging within 205,000 acres of Pacific Lumber holdings in Humboldt County. The state requires a “sustained yield plan,” or SYP, as well. [Sustained yield means that the rate of harvesting does not exceed the rate of new growth.] The federal and state governments, for their part of the deal, must approve or deny the company’s HCP and SYP plans within 10 months.

Some say a scientifically sound habitat conservation plan cannot be completed in 10 months. However, the Department of the Interior’s own guidelines specify that HCP’s should take no more than 10 months to complete, and the environmentalists are welcome to participate in the process by reviewing and commenting on any plan submitted by Pacific Lumber before it is approved.

As part of the accord, Pacific Lumber has agreed not to conduct any logging operations, including salvage logging of dead and dying trees, in the 7,500 acre area during the 10-month period while the agreement is being finalized and the habitat conservation plan developed.

Concluding Statements on Headwaters

Wood Products Industry (The Pacific Lumber Company):

“Parties to the Agreement agree that preserving the 7,500 acres is appropriate from a scientific standpoint and is practical in terms of what can be accomplished. Demands from various activists that approximately 60,000 acres of Pacific Lumber’s timberland (nearly one-third of its total land resource) be preserved are not justified by science, are not practical, and are not of interest to the company…” —“The Headwaters Forest: A White Paper,” The Pacific Lumber Company, March 1997

Environmentalists (Headwaters Sanctuary Project):

“Is the deal justified? And more importantly will it protect all of Headwaters Forest? The jury is still out. If Charles Hurwitz walks away with $380 million and the right to cut most of the rest of the forest, it clearly is not. If President Clinton and Senator Feinstein insist on a Habitat Conservation Plan that protects all 60,000 acres of Headwaters Forest it surely is. With just four percent of the ancient redwoods left in the world, the high price is justified.” — Communication Works, August 1997

Dianne Feinstein U.S. Senator from California:

“This compromise offers our last and best hope to preserve these magnificent redwoods. If the plan goes forward, the Headwaters Forest will become a treasured federal and state preserve—and the largest habitat conservation plan in history will be implemented. Jobs will be saved, the forest will continue to provide ample habitat for endangered species like thte marbled murrelet, and our children will be able to experience a small part of the virgin forests that once carpeted the West Coast.” —San Francisco Chronicle , October 7, 1996 What Will it Mean for Old Growth Forests?

On November 14, 1997, President Clinton signed a bill containing $250 million to buy 7,500 acres in the Headwaters Forest. This fulfilled the federal government’s part in the agreement to preserve some of the ancient redwoods owned by The Pacific Lumber Company. The next step is up to the State of California. California’s Governor Wilson offered several large parcels of forested land in exchange for the old growth forests owned by Pacific Lumber, but these offers were turned down. The next step will be to ask California voters if they are willing to pay the additional $130 million to complete the deal. Given that the voters turned down an opportunity to buy the Headwaters grove in 1990, the results are by no means guaranteed. What will it mean for the wildlife that lives in the remaining old growth forests when these forests are logged? How will the soil and climate be affected? How will it affect the fish in rivers and streams that flow through the forests? Unfortunately, no one has final answers to these and related questions. However, you’ll see in the next chapter that scientists are hard at work trying to find the answers.

From San Francisco Chronicle, Feb. 13, 1998

Approval of the HCP is being held up because biologists with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service believe that protecting all of the ancient groves is critical to the survival of the local population of marbled murrelets. Negotiations continue. The California vote on whether or not to contribute the additional $130 million is set for June, 1998.

Get more recent updates from the World Wide Web:

Pacific Lumber Company – http://www.palco.com

Earth First! – http://www.envirolink.org.

AN3.2. Investigation: Write A Letter To the Editor

It is time for an election in California. Write a Letter to the Editor of a California newspaper urging people to vote for or against using $130 million of taxpayer dollars to complete the Headwaters Agreement.

In composing your letter, be sure to answer the following questions.

- What is your message? That is, do you want people to vote “For” or “Against” paying $130 million to The Pacific Lumber Company to preserve the forest?

- Why is this vote important? In other words, what principles do you think are at stake here?

- What do you think should be done about old growth forests and why?